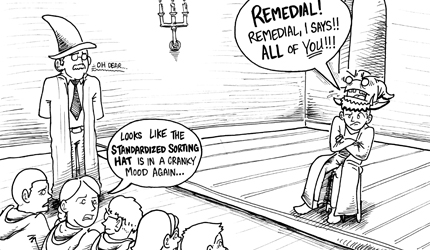

It looks like the accuracy of the ACCUPLACER placement test isn’t quite cutting it. And the COMPASS test isn’t sending all students in the right direction.

But that might not be solely the test makers’ fault.

Between 21 and 33 percent of students who took the tests in two community college systems were “severely misassigned” to English or math courses, according to two studies conducted by The Community College Research Center at Columbia University’s Teachers College. This means either the students were routed for remedial courses though they were expected to get at least a B in the regular course, or they were placed in the regular course though they were expected to fail it.

One of the studies examined an urban community college system, and the other examined a two-year statewide community college system.

While the research is not entirely conclusive, it does signal a need for further investigation into the tests — and others like them — and into the way colleges determine which students need remedial courses.

In an article on the research, Inside Higher Ed states that experts believe remedial education is “the primary obstacle to more students earning college degrees.” Remedial courses often can’t be applied to a student’s degree plan. And the number of students receiving remedial education and also earning a degree from a community college or moving on to a four-year college is low — just 25 percent, according to Inside Higher Ed.

So while remedial education is intended to get students on track, it appears that it can also contribute to their failure to graduate from college. This makes it even more important to determine with greater certainty whether students really need the courses in the first place.

Though the researchers found high school grade point averages could give more accurate placements than the placement exams, one researcher suggests looking at both indicators is a better method than looking at just one or the other, according to a New York Times article on the research.

But there also appear to be problems outside of the tests themselves.

The New York Times points out that oftentimes students don’t really know how important these placement tests are. They “are told that they need not worry about the tests” and they aren’t told they should study for the tests as they would for a college entrance exam, the Times reported.

If students don’t put sufficient effort into the tests, or make sufficient preparations prior to taking them, it’s certainly not a stretch to believe they might be put in remedial classes they don’t truly need to take.

In that situation, the responsibility falls on instructors and universities to ensure students know exactly what these tests mean for them and how they could affect their college careers. Then, of course, the responsibility falls to students to adequately prepare, and to take the exams seriously on test day.

So improvement is needed on all sides — from test makers to the students themselves to the universities who make the final call on where students are placed. But we also need more research, not only on placement tests, but other standardized tests as well.

College readiness tests, such as the ACT — which was created by the same company as the COMPASS test — and the SAT have grown to such importance in recent years that we’ve seen scandals and acts of desperation by both universities and individual students trying to get their scores where they want them.

But questions about the validity of college placement exams should give us all pause. If these tests do not indicate exactly what we think they should, that’s a cue that we should re-examine other standardized tests as well, and possibly start placing more emphasis on other factors, such as GPA.

It seems we have gotten too caught up in what the test scores are supposed to mean, and have failed to make sure that the tests and testing system are as accurate as they possibly can be. This problem affects students’ pocketbooks, their college experiences and, most importantly, their futures.

But many colleges have already been looking for ways to address the problems they perceive to be associated with placement or diagnostic tests, according to the New York Times. They’re changing math requirements, for instance, to better match the skills students actually need for a specific program. Or changing the structures of their remedial programs so students can continue their degree program while taking the remedial courses over their lunch breaks.

These are important steps toward making college a more student-friendly experience. With more research into both testing and remedial education, the system could see even greater improvements in the future, and an increase in qualified college graduates, which, after all, should be the ultimate goal.