Associated Press

By Lise Olsen

Houston Chronicle

HOUSTON — The woman’s nude body was found floating in the muddy Brazos River in 1975, her features unrecognizable save for her flawlessly painted scarlet fingernails and flowing yellow hair.

But after 37 years, the 22-year-old mother has been identified by Harris County forensics experts as Gloria Faye Stringer, opening an investigation into her possible murder and inflaming the long-held suspicions of Austin County Justice of the Peace Dennis R. King, a man committed to the case for decades.

“The only thing worse than dying in a strange place is being lost at the same time and never finding your way home,” King said. “That was always the fear for me — that she had not been able to find her way home.”

Stringer had recently relocated to Texas City, leaving her 6-year-old son with grandparents in Tennessee, before vanishing in 1975.

King and Austin County Sheriff’s investigators will try to determine how a woman who owned no car and couldn’t swim ended up naked and dead in a river 87 miles away from her last known address. Among other theories, officials are looking at whether her death is linked to the unsolved serial killings of young women and teens abducted from the Houston and Galveston areas in the 1970s.

It was King who helped recover Stringer’s body in 1975 and who had her bones exhumed in June 2009 hoping a forensic artist’s reconstruction of her face or DNA evidence might result in identification.

“He never gave up,” said Scott Minyard, a corporal who got permission from the Austin County Sheriff to join the investigation in 2010. “Different sheriffs got elected, deputies retired or moved on and part of the file was lost … if King had died or left office this may never have been solved. But once he reopened the case it took a lot of teamwork and cooperation to put it all together.”

Stringer last phoned home on June 4, 1975, saying she planned to travel to Houston. Three days later, boys fishing near their subdivision in Sealy spotted a body afloat in the fast-moving Brazos River, about two miles upstream from where the river crosses Interstate 10, said King, who arrived at the scene as a 29-year-old rookie in his first year as justice of the peace.

“We had to go out into the water and pull her ashore,” King recalled. “She was a Jane Doe. With the type of systems we had back in 1975, there was little we could do other than just calling around to see if anyone was missing.”

Officers found no clothing or a car in searches of the riverbanks. There was no matching missing person’s report. Reluctantly, King authorized a county burial in a pauper’s grave. It was King’s first — and for 37 years remained his only — unidentified death victim as justice of the peace in Austin County, about an hour west of Houston.

He never stopped working the case. In 2009, he placed his hopes in forensic science. King successfully petitioned for funds to exhume the body and asked a skilled forensic artist to use the skull to sketch a likeness. Then he hand-delivered bones from the body to the University of North Texas’ DNA Identity Lab in Fort Worth.

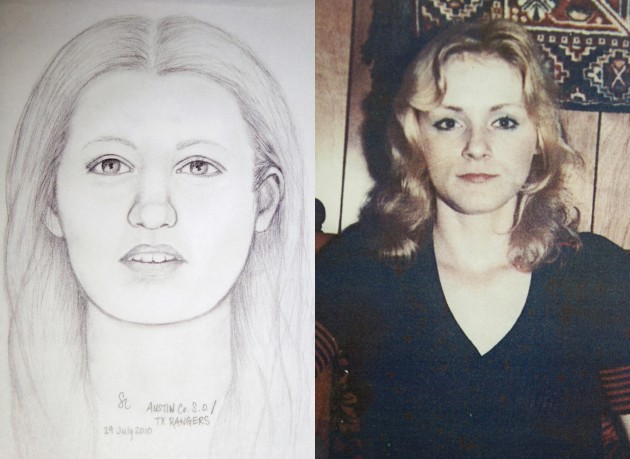

Attempts to extract DNA proved unsuccessful. But an artist for the Texas Rangers, Suzanne Birdwell, produced a portrait of a 19-year-old with a pug nose, large pouting lips and widely-spaced oval eyes whose face was framed by a popular 1970s hairstyle. That image and case summary appeared on websites for missing and unidentified persons in 2010.

On June 7, 2011 — the 37th anniversary of the body’s discovery — King, Minyard and others gathered to place a plaque on the still-unmarked grave. King offered a prayer: “I wanted for it to happen before I retired or before I died.”

Afterward, Minyard dropped by the sheriff’s office to find a telephone message from Tennessee. The caller was Sandy Stringer, whose sister-in-law Gloria disappeared in Texas in July 1975.

All the elements matched: height, weight, age. Both had their spleen surgically removed. Soon, Minyard reached Stringer’s only son, Dan E. Moore.

Moore had been only 6 when his mother disappeared. Their last portrait shows him smiling beside her: They share the same pale hair and oval eyes. In the photo, her long manicured fingernails are painted scarlet — the same shade King spotted on the body in the river.

Moore is now a Tennessee Highway Patrol lieutenant who supervises criminal investigations. Over the years, he combed police reports and countless archives. Then in June 2011, his aunt told him to check the sketch of a woman she found on a Texas Department of Public Safety website.

Finally, a combination of 11 clues helped convince Jennifer Love and Dwayne Wolf of the Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences to positively confirm Stringer’s identity earlier this month.

“I don’t know how many hundreds or thousands of pictures that I’ve looked at since the Internet came around — always looking for my mom’s face,” Moore said. “… But when I clicked on this one that night, I just knew.”