Luke Lattanzi | Staff Writer

From 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday, zookeepers at the Cameron Park Zoo rarely get a moment off their feet, spending the vast majority of their time training and caring for the more than 1,700 animals across over 300 species currently housed within the zoo’s boundaries.

Founded as the Central Texas Zoological Park in 1955 and renamed the Cameron Park Zoo in 1993, the 52-acre attraction sitting at the junction of the Brazos and Bosque Rivers has remained an integral part of the Waco community.

Despite its area, the zoo remains relatively small compared to other zoos across Texas — a feature zookeeper Brittany Eckenrode, who specializes in working with hoofstock animals like deer or rhinos, views as beneficial for communication between staff members.

“We know aquatics. We know reptiles. We know grounds and maintenance,” Eckenrode said. “Whereas in larger facilities, since they have more staffing in bigger areas, they can tend to be [disjointed] in the keepers knowing each other, knowing the maintenance workers, knowing grounds, knowing custodial staff, knowing admissions.”

Zookeeper Allison Wirt, who specializes in caring for birds and small mammals, said the zoo’s size is conducive to “camaraderie and teamwork,” as zookeepers from different exhibits, despite their individual specializations, are able to provide additional assistance if needed.

“I mean, just a few weeks ago, we came and helped [zookeepers] with some mulch at [the rhino exhibit], and we’ve had to do a big catch-up in our short bird aviary,” Wirt said. “It’s all hands on deck with keeper staff.”

While most zoos require an associate’s or bachelor’s degree in the hard sciences, the vast majority of the skills that zookeepers need to learn come from hands-on experience. Wirt, who majored in animal science at Ohio State University, said only so much can be learned from inside a classroom.

“Beyond the degree, a lot of it comes from practical experience,” Wirt said. “Internships are really important to getting into the field, like seasonal zookeeper type jobs, which are usually paid but temporary.”

Zookeeper Brian Chen, who studied wildlife conservation at the University of California, Davis, said he started off doing research and field work, where he observed the behavior of animals. During COVID-19 when jobs were scarce, he found an apprenticeship at a zoo in California and grew to love working with animals. Much of Chen’s research and field work was also focused on birds of prey, such as owls, helping him find his niche in the zoo’s bird habitats.

“I did that, and I absolutely fell in love with the whole training aspect of being able to work [in] close quarters with animals,” Chen said. “And after that, I did a couple other jobs in between, but then it’s like, ‘Here I am.’”

A lot of Chen’s initial training came from watching how the animals behaved.

“I just spend a lot of time kind of just watching how they interact [to] try to, in a sense, experiment,” Chen said. “If I do this, what would they do? If I do that, what would they do? And kind of learn from there what types of behaviors that I can do without either harming, hurting [or] scaring our animals while still getting the [experience].”

Eckenrode said she also learned from observing others who were more advanced than her in training animals and learning their behaviors.

“A lot of things I learned is patience with an animal,” Eckenrode said. “Specifically for hoofstock, a lot of them are prey species, and they have fight or flight. So the first step for us is [desensitizing] them to our presence or [desensitizing] them to a specific thing.”

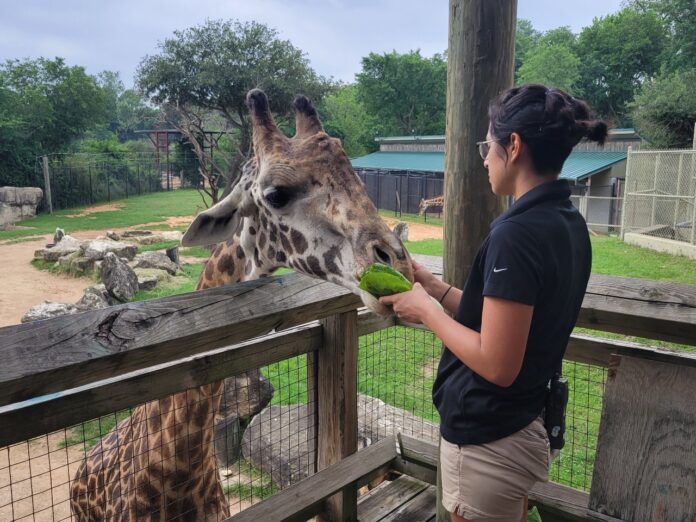

Eckenrode said gaining the trust of animals can be achieved through hand-feeding or just spending time with them to acquaint them with human presence.

For Wirt, it depends on which species she is working with. Specializing in working with birds means learning specific capture techniques in order to properly care for the birds, such as trimming their nails.

“For birds, we can use nets. We can use blankets. Sometimes you’re just catching something by hand,” Wirt said. “You also want to learn how to hold a bird, because some birds you kind of hold almost like a football. … Like flamingos, for example, you kind of hold like a football with their heads behind you and you hold onto their feet.”

Regardless of what type of experience it may be, Chen said new zookeepers coming into the field shouldn’t be afraid to try, and it’s never too late to get the training and experience needed.

“Experience is there for you to gain,” Chen said. “It’s not like [if] you’re older, you can’t gain anymore. Don’t be afraid to move around and try out different internships, different areas — and not just within one facility. You can try different facilities within your city or out of your city, out of state even.”

Wirt also said new zookeepers shouldn’t get too hung up not knowing which animals they want to work with. While she specializes in birds now, she has also explored working with primates and carnivores.

“I think it’s helpful to work with a variety of things, because you never know what you’re going to fall in love with,” Wirt said.

Chen said in the end, being a zookeeper all comes down to being willing to learn.

“Just be open,” Chen said. “I think most people that love animals, it’s the same way. Sure, we have one or two or many that we like, but we would love to learn about all of them.”