Since the increased popularity of the Enneagram test, knowing someone’s number allows us to form assumptions about the personalities of people around us. The Enneagram can reduce complex, unique people to a simple personality type. While tools such as the Enneagram help us learn about ourselves and relate to those around us — especially since college is prime time for self-discovery — they should never be used in isolation or taken at face value.

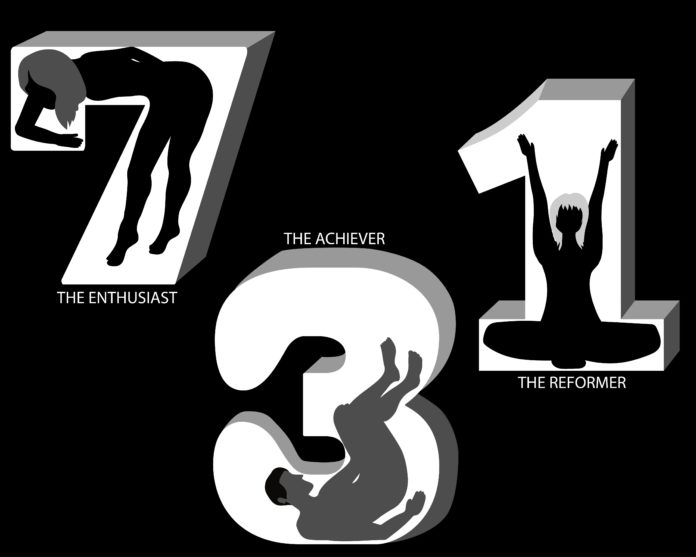

The Enneagram, a test that identifies nine personality types, has risen to popularity recently. It identifies people’s prime processing methods — thinking, feeling or instinctive — as well as responses to losing sense of self — anger, fear or shame. Through mixing and matching these features, nine personality types are created.

The test identifies levels of development with predictions of what one may look like when moving toward growth versus under stress and pressure. Its insights have allowed The Enneagram to be adopted into job applications, Christian discipleship and life coaching practices.

In more informal settings, the Enneagram has also been used for individuals to better understand themselves and their peers.

By outlining response patterns, the Enneagram calls attention to subconscious tendencies within people. An increase in self-awareness can bring more controlled behavior. The Enneagram is arguably a good source for steps for development, because advice is personalized rather than generalized.

The danger to applications of the Enneagram, and similar personality assessments, is basing judgments of self and others solely off given prescriptions. The Enneagram Institute admits its own limitations on its website: “Individuals are understandable only up to a certain point beyond which they remain mysterious and unpredictable.”

Although the test does well recognizing the fluidity of personality, evident in its descriptions according to situation and maturity, it still constrains people to types.

The complexities of an individual cannot be reduced to a number. Our editorial board is made up of 2, 2, 3, 4, 7 and 8. Just given this information, you might be able to gather a deeper understanding of each of us, but there are intricacies within our personalities that cannot be contained within a simple one-digit number.

The Enneagram Institute said on its website that its types are mainly determined by “inborn temperament and other pre-natal factors.” While genetic factors greatly contribute to personality, they are not the only influences to consider.

A Journal of Personality and Social Psychology study on transitions of adulthood between ages 18 and 30 “links personality changes with contextual conditions such as work and romantic relationships.” While genetic factors were found to account for traits, the expression of those traits — ultimately culminating in behavior — were an “important influence” over time.

Because each test has its own aspect of the human character it seeks to describe, we should use a combination of tools to assess and grow in understanding of ourselves. Supplementing the Enneagram allows for exploration of other personality facets.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, for example, creates types based on behavior rather than internal responses like the Enneagram. The StrengthsFinder helps users identify their strengths, giving strategies for applying and building your natural talents. Finding discrepancies between different test results can also help recognize the flaws within each system.

Tests will inevitably miss the mark on certain things, and therefore shouldn’t be used to define a person but rather help a person define themselves. These assessments are guides to adapt to individuals, not for individuals to adapt to.

We should be wary of the need to fit our personality type. It isn’t a number on the Enneagram or a four-letter Myers-Briggs combination that defines us. People are far too complex and capable of growth to be constrained to such a static variable. Make the effort to get to know yourself, not your type description.