Every morning across the United States, children say “one nation under God” as they recite the Pledge of Allegiance aloud in public school classes. Every day, students buy items from the vending machines using U.S. $1 bills, which say, “In God we trust.” On Aug. 9, Rick Perry declared a day of prayer in Texas.

Are one of these things really not like the other?

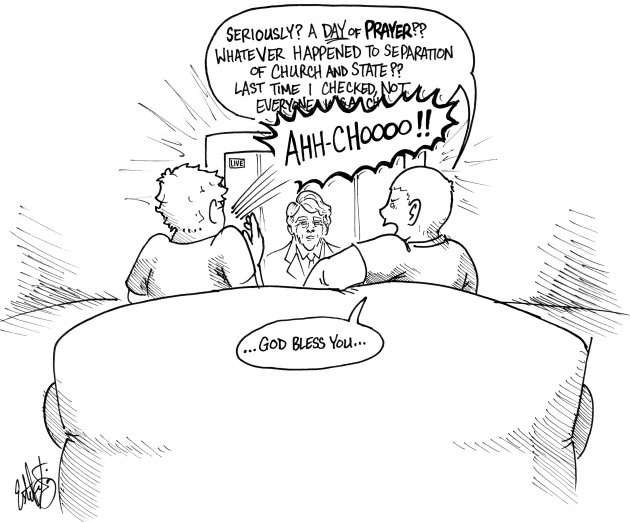

Some Americans say yes, arguing the national day of prayer violates separation of church and state, further claiming the event is a publicity device for Perry’s 2012 GOP nomination. The question then is, what makes a day of prayer unconstitutional, but swearing on a Bible in a United States courtroom acceptable?

The answer is simple when we realize the issue really lies in politics. The progressive advocacy group, People For the American Way, called the event “inappropriate” while the American Family Association, a conservative Christian group that funded the event, said the day was meant to foster “acceptance.”

Billed as a day of prayer and fasting, the Aug. 6 event drew some 30,000 people, with Perry leading prayers asking for an end to the drought and decline of America, among other things.

It’s easy to see why a Christian prayer summit would drum up feelings of alienation from non-Christian groups. Perry, however, insisted the day was open to all faiths. What makes Perry’s day of prayer different than requiring a sworn oath to one’s God at the presidential inauguration? Will anyone object to Perry’s right hand on the Bible if he happens to be standing on the Capitol steps on Jan. 20, 2013?

The question of whether Perry’s day of prayer was from the heart or politically motivated could be discussed forever. In the midst of the criticism, though, it is important to note that historically, leaders have come before God in times of trial or need.

During the drafting of the Constitution in 1787, Benjamin Franklin asked the framers to join together and pray for direction, saying, “I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth – that God Governs in the affairs of men.” Franklin continued. “I therefore beg leave to move – that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business.” It seems as though Mr. Franklin would have found himself in Perry’s boat if alive today.

In Perry’s proclamation of Aug. 6 as a day of prayer, he refers to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s prayer during World War II asking for “thy help to our efforts” while our troops were “locked in battle on the beaches of France” on June 6, 1944. Is a president’s prayer in wartime anymore a violation of church and state than a governor’s prayer during a famine?

Of course critics questioning Perry’s possible political motivation will point out the biggest difference between Roosevelt and Perry – one man was President and the other isn’t. Even reports like one from the New York Times, which said Perry envisioned the prayer day last December, won’t be good enough to spurn the accusations.

Now Americans on both sides are left asking where we draw the line in the sand. For now, the answer remains to be had. However, perhaps what we can agree on is acceptance should never be unconstitutional.