By Matthew Muir | Staff Writer

A Baylor environmental science professor played a starring role in a global webinar discussing how to prepare for public health disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Benjamin Ryan, clinical associate professor of environmental science, joined a panel of other health experts to present “Resilience of local governments: A multi-sectoral approach to integrate public health and disaster risk management.” Presented by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), the webinar drew just shy of 1,000 participants from around the globe.

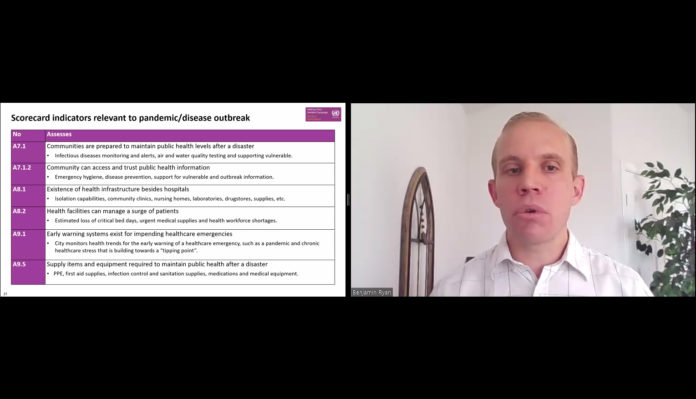

Ryan focused on implementing the Public Health System Resilience Scorecard: a system to measure a city’s level of preparedness for a public health emergency. Ryan said understanding how all the moving pieces of our public health systems interact is key to proper preparedness.

“Our public health system is not successful without all the different factors, so it’s multi-sectoral,” Ryan said. “We really need to highlight that for us to be effective as a society in providing good public health services. We need to consider a whole of society approach.”

The public health scorecard is itself an addition to the UNDRR’s Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities, and the UN now recommends cities plan for public health emergencies the same way they would plan for emergencies such as natural disasters.

Dr. Peter Williams, an IBM Distinguished Engineer and lead author of the public health scorecard, said the public health scorecard was written to help address the public health implications of major disasters such as floods and earthquakes.

“But it’s evident above all now that pandemics share the depth and breadth of impact of other disasters. They’re every bit as catastrophic as a major earthquake or as a major flood,” Williams said. “Therefore, an instrument that deals with the kind of impacts that a flood or an earthquake can have … may prove useful for dealing with a thing like the coronavirus, and indeed other pandemics that arise in the future.”

The scorecard assesses all facets of a public health system to determine which areas need improvement. These include how public health issues are addressed in disaster risk plans, if emergency funding is readily available for public health services, even if medical records would be accessible during or after a disaster. Ryan said the scorecard helps draw the focus to “what the community needs to function,” and local officials can tailor disaster response plans to their community’s specific needs as a result.

“The fantastic thing is you can identify your strengths and weaknesses, and it’s important to know both of those during a disaster so you know where to allocate your resources,” Ryan said.

Ryan gave the example of Cairns, Australia which was force to evacuate hospital staff and patients roughly 1,000 miles by road ahead of a tropical cyclone. Due of this, the local government identified the need for a facility which could safely house patients through a such a storm.

A facility in Cairns is now being built to withstand a category 5 cyclone to solve this exact problem. Ryan said the scorecard encourages similar kinds of adaptations in the face of a crisis.

“The benefits of the [public health scorecard is] really the conversations that are generated,” Ryan said. “These fantastic discussions that come out … you will not see these if you do not have these discussions in the time of a crisis.”