Black Americans, we will destroy our cities before the police do.

The kind of turmoil, which is not as widespread as the media would have us believe, that erupted in Baltimore on Monday is becoming a disturbing habit in the wake of black deaths at the hands of U.S. police officers.

The city of Baltimore was the site of protests earlier in the week in response to the death of Freddie Gray, as well as what city officials said was a long history of racial tension in Baltimore. Gray died on April 19, but the details surrounding his death are unclear.

Reports from CNN say Baltimore police officers approached Gray at 8:39 a.m. on April 12; the reasons for this encounter are still undisclosed. Police say Gray then fled. They then take Gray into custody at 8:40 a.m. At 8:54 a.m., he is dragged, screaming, into a police van. At 9:24 a.m., the officers request medical attention for Gray.

For the next week, Gray was in a coma resulting from a mysterious spinal cord injury until his April 19 death. Six officers have been suspended while the investigation is carried out, but the details of how each officer contributed to the event have not been released.

Gray did have a criminal record, but it is unknown whether this played a role in his encounter with the officers.

Baltimore police say the investigation’s results should be concluded by Friday, although it’s unlikely the findings will be released to the public on the same day.

While hundreds of peaceful protesters took to the streets to express their frustrations in a respectable manner, a smaller group of Baltimoreans, primarily young blacks, responded to the event with looting, arson and violence against police Monday evening.

Baltimore police and the National Guard made more than 200 arrests, six officers were seriously injured by rioters, and more than 20 businesses and 144 cars were set ablaze.

I get it. Black Americans, especially those who live in cities with a history of conflict between minorities and police, are angry.

They are tired of having to live with the attitude that simply their presence is enough to warrant being stopped by unscrupulous officers. Black mothers are tired of teaching their sons to live with their eyes on the ground and their hands out of their pockets so as not to look delinquent.

They’re angry, and they have a right to be.

The flame of that anger, however, has to be kindled in a constructive, controlled manner. The details surrounding Gray’s death are extremely ambiguous, and what we do know doesn’t for sure pin his death on anyone.

No one but the officers in the van know what happened, which means we can’t blindly burn a city down.

That being said, even if we all saw Gray killed with our own eyes, I still couldn’t support the small group of rioters. Although all the riots of the past year are bringing police brutality to the public eye, not everyone is seeing the issue in the same way.

The stereotype of minorities being thugs is only further solidified when young black men in hoodies are throwing cinder blocks at rows of police officers as others set fire to convenience stores.

What many people watching the news often forget is that the media only focuses on what will keep people appalled — and watching.

There weren’t very many outlets reporting about the plethora of black Baltimoreans pleading with their peers for nonaggression. There were no images of police and black citizens interacting peacefully.

Even one of the most positive stories to come out of the Baltimore riots involves violence: a mother was caught on video repeatedly hitting her masked son in the middle of the street when she realized he was contributing to the disorder.

There is something to celebrate in the fact that minority mistreatment by select police officers is being brought to the light.

But as this happens, blacks’ actions cannot move further and further into the dark. There is no justice to be found in the toss of a bottle or the strike of a match.

There is no peace living in the destruction of cities we all call home.

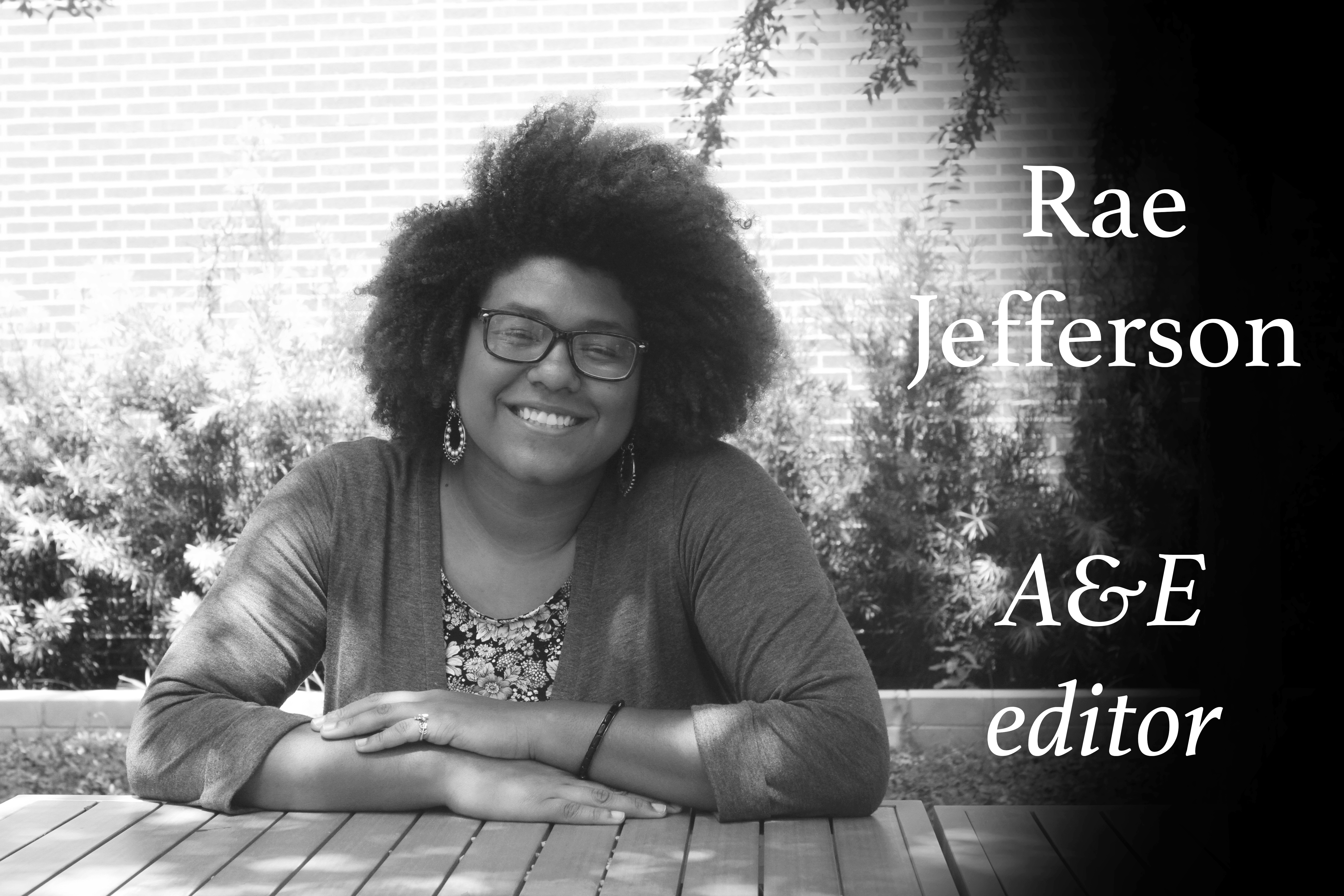

Rae Jefferson is a junior journalism major from Houston. She is the arts and entertainment editor and a regular columnist for the Lariat.