By McKenna Middleton | Opinion Editor

When faced with a piece of modern art, the temptation is to think to yourself, “I could have made that.” Conceptual art can often bring us outside of our comfort zone because it causes us to question what art really is.

The statement “I could have made that” suggests a valuation of technical skill over any other artistic component. This line of reasoning makes sense. After all, if something is going to be worthy of a museum, it should be something that transcends the abilities of the average museum-goer. While conceptual art doesn’t surpass the physical technique of Renaissance painters, its name suggests its true purpose. Conceptual art is based on suggesting a concept. That is to say, it doesn’t matter if you could have made that because you didn’t.

The importance of creating art that most closely resembles reality, such as portraiture, has ebbed and flowed throughout the history of humanity. After the advent of the camera, for example, artists were faced with an unforeseen dilemma: If photography can perfectly replicate reality, what is the role of artists? Why spend years mastering the technical skill required to reproduce images on a canvas if photography can instantaneously reproduce them?

What could have been a competitive limitation for artists has actually liberated them. Now, art could be non-representational. This has produced art movements like impressionism that sought to depict the world in a new way rather than reproduce reality.

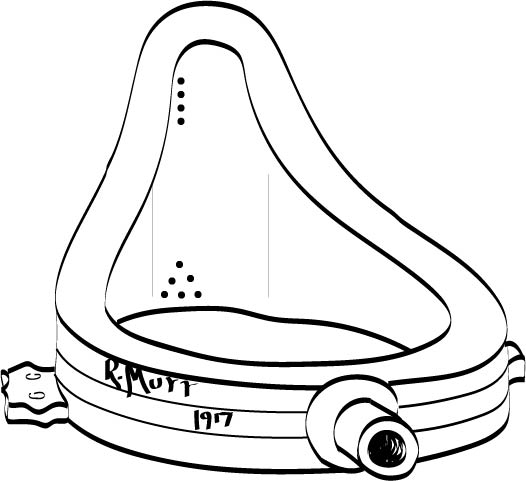

Perhaps the most infamous early conceptual artist, Marcel Duchamp, took this idea of non-representational art further than ever before. In 1917, Duchamp submitted a new art piece to the Society of Independent Artists, which he had helped found on the principle that all members’ submissions must be accepted and displayed. The piece, titled “Fountain,” caused great controversy for one reason: Duchamp did not make the piece by his own hands. In fact, the artwork he submitted was simply a urinal he had purchased from a sanitary supplier.

“Fountain” caused such an uproar due to the association with bodily waste and the fact that it was not created by Duchamp himself that the Society of Independent Artists made an exception to their constitution by voting to exclude the piece from its show.

Rewon Shimray | Cartoonist Photo credit: Rewon Shimray

This type of art is called a “readymade,” and it is a type of conceptual art. Duchamp wanted to challenge the artistic elitism of his time through this piece. “Fountain” sought to question the boundaries of art and suggested that art holds value because of the artistic concept behind it rather than the artistic process that goes into crafting it.

Since then, modern artists have embraced this idea of conceptual art. One hundred years after “Fountain,” conceptual art still causes controversy.

In 1936, Surrealist artist Meret Oppenheim bought a teacup and covered it with the fur of a Chinese gazelle. She wanted to juxtapose an object with perceived feminine qualities (a teacup) with an object with perceived sexual and passionate qualities (fur).

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s 1991 piece, “Perfect Lovers” is two synchronized office clocks placed side-by-side. Like Duchamp, Gonzalez-Torres’s piece holds value not because of the objects themselves or the technique that went into their creation, but rather the philosophical principles the clocks represent. In the case of “Perfect Lovers,” Gonzalez-Torres sought to demonstrate the tension he felt as he watched the person he loved most move towards death as a result of AIDS. He used clocks as a metaphor for this idea in that even two clocks may stop being synchronized if the battery in one runs out before the other.

Of course, a museum-goer would not necessarily be able to gather Gonzalez-Torres’ or Duchamp’s concept simply by viewing their art. Some opponents of conceptual art argue that art shouldn’t need plaques next to them to explain their meaning. They prefer a piece of Renaissance art such as Michelangelo’s “David,” in which the viewer can clearly see that the artist wishes to depict a biblical narrative. However, no piece of art can truly be understood outside of context. Without the context of the story of David and Goliath, “David” would lose a significant element of its artistic purpose.

Even the claim that conceptual artists lack technical artistic skill fails to recognize the fact that most conceptual artists attended art school and can demonstrate a mastery of many different art forms. For example, the early works of Spanish painter Joan Miró are extremely detailed. Later on in his career, he began to align with the Surrealist and readymade movements, announcing a “death to painting” (“quiero asesinar la pintura). His work then began to include sculptures made of found objects like string and feathers.

Ultimately, the claim, “I could have made that,” really just reveals a personal value: a conclusion that technical skill is more important than individual philosophic thought. This could be compared to valuing architectural skill (based on concept) over constructing skill (based on technique).

It’s not that conceptual art doesn’t require skill; it just requires a different type of skill. Conceptual art is not about what the artists present or how they create it, but rather why. The goal of a conceptual artist is to encourage viewers to ask questions and consider the context. Instead of saying, “I could have made that,” consider asking, “Why did the artist make this?”

McKenna is a senior journalism and Spanish double major from Glendale, Calif.