The Bottom Line | A Student Economist’s View

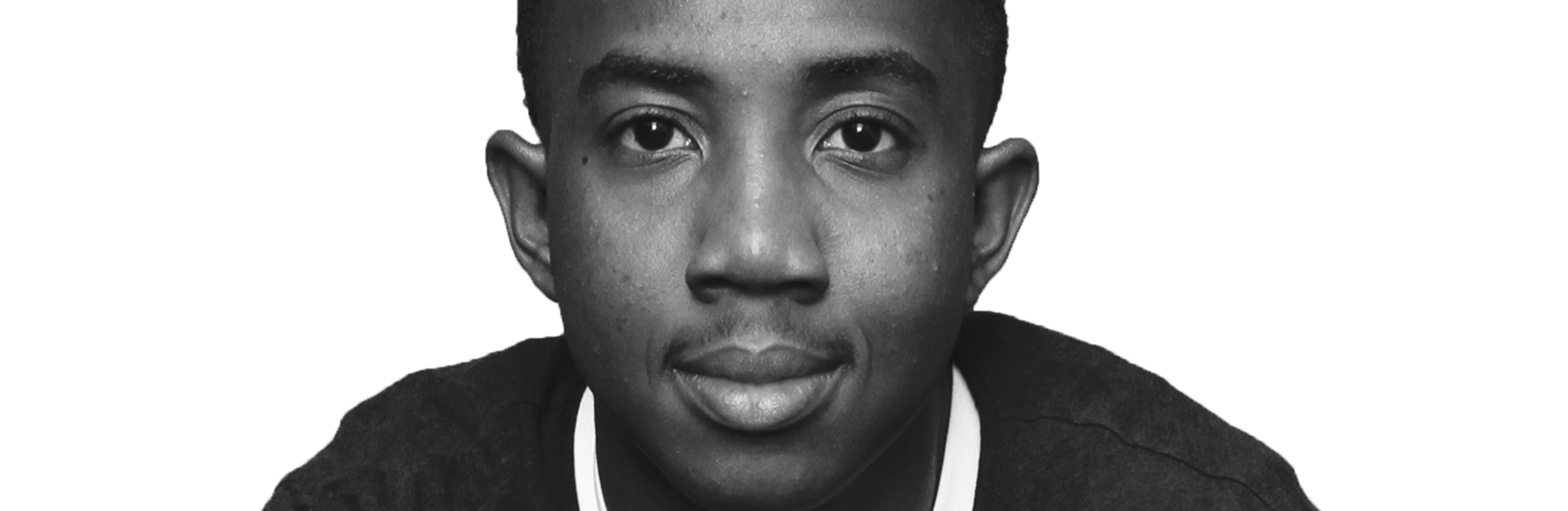

By Reubin Turner

City Editor

Last week, Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen testified before Congress and was questioned by Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Rep. Jeb Hensarling who serves as chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, and others. During the hearings, Yellen was asked about inflation, the unemployment rate and the Federal Reserve System’s top legal counsel. At the hearing, Yellen made one thing abundantly clear — interest rates aren’t ready to go up, and the Fed will not raise them yet. Some lawmakers disagree with Yellen about whether or not to increase interest rates and out of frustration, are working to get bills through Congress that would make Yellen more accountable for the Fed’s actions. Before passing such legislation that would ultimately reduce the autonomy and power of the Fed, however, Congress should consider the consequences political interference could have on the nation’s highest economic policy-making institution.

When the Fed was created in 1913, legislators were clear in their intent to create an institution that could effectively guide the nation’s economy without political distractions. Instituting policies that call for the head of the Fed to be appointed rather than elected and establishing that the Fed’s board of governors do not have term limits all help ensure that the leaders of the Fed are not subject to the political pressures of the day. They could make decisions based on their experience and superior knowledge of economy. Nothing else.

This idea of subjecting the Fed to Congress even in the slightest of ways threatens that entire idea. The Fed’s viewed power has increased tremendously since the 2006 Great Recession, but as former Fed governor Sarah Raskin stated in a hearing to Congress, they did nothing that was outside their scope of authority. Desperate times call for desperate action, and the Fed had to take unprecedented action to prevent economic calamity.

Perhaps its Yellen’s refusal to adhere to the Taylor Rule that Congress disapproves of when it comes to the Fed’s policy decisions. The Taylor Rule is a rule proposed by economist John B. Taylor that determines how much the Fed should change the nominal interest based on economic conditions, like inflation and real GDP. Yellen said last week that although she agrees with certain principles set forth in the rule, the Fed will not be “chained” to a formula when it comes to monetary policy. Yellen stressed that she was not a proponent of the rule in 1995, and 20 years later, she stands by her choice. And if I’ve learned anything as an economics student, it’s that this is probably a wise decision on Yellen’s part.

Variables within the nation’s economy, and life in general, make it extremely hard to follow a strict rule. If it was as simple as this, make me the next Fed chair. I think I could manage a 2+2=4 approach to monetary policy. But I along with Yellen, agree that it’s not that simple. Years of training in the field, study and a great intuition are needed for a job like Fed chairman. Yellen’s Ph.D. in economics from Yale, coupled with her experience as the vice chair of the Fed and chairman of the board in San Francisco, qualify her quite well for the position. In addition to her credentials, Yellen was credited by her nominator, President Barack Obama, and other peer economists as “sounding the alarm” of an impending financial crisis if policy did not change in the housing markets. A formula can’t tell you that. Only experience and intuition can.