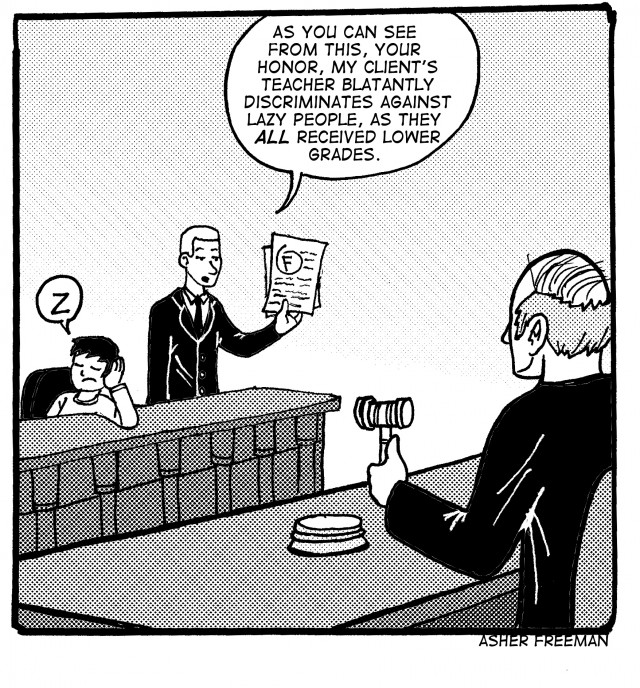

Most people don’t mean it when they say, “You don’t like it? So sue me.” But one graduate student who didn’t like her grade did just that.

Most people don’t mean it when they say, “You don’t like it? So sue me.” But one graduate student who didn’t like her grade did just that.

A judge recently ruled against former graduate student Megan Thode, who was suing Lehigh University for $1.3 million in damages as well as to raise a C-plus grade she earned in a class that was mandatory to earn her master’s degree in counseling and human services. Thode claimed the professor of the fieldwork class discriminated against her because she agrees with same-sex marriage and the professor does not.

The judge decided Thode did not provide enough evidence to support her discrimination claim and said she saw no reason to believe Thode’s grade was given for anything other than Thode’s academic performance.

However, had the judge ruled in Thode’s favor, her C-plus grade would have increased and she would have received $1.3 million in damages, which is the amount Thode claimed she would have made in salary as a therapist if she’d been able to get her license in therapy. Thode graduated with her master’s degree in human development and has a job as a drug and alcohol counselor.

We believe the judge made the right decision in this case because a dangerous new precedent could have been made. By a ruling in Thode’s favor, it could cause our ability to sue and be sued to spiral out of control.

Thode is not the first student to attempt to increase her grade by way of a lawsuit, and she probably will not be the last.

In 2007, a student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst sued after receiving a C and the case was dismissed. In 2013, two Texas Southern University’s Thurgood Marshall School of Law students sued after receiving Ds. Each of these cases were dismissed.

If judges rule in the favor of the plaintiff in cases such as these, they could set a precedent for future cases. A new pattern could emerge of lawsuits brought against universities for subjective grades and the plaintiff wins.

It’s easy to make the case that some grades given in college or graduate school are subjective. Because grades measure activities like critical thinking or writing skills and are given by humans, that element of subjectiveness will always occur while professors are grading papers, tests or other work. It’s why only those who have studied extensively can become professors — they must have the knowledge themselves to grade the works of others effectively.

Discrimination, of course, is wrong. But subjectiveness? It happens.

If Thode were to win a lawsuit that would retroactively change a given grade, it seems almost any student could sue for better grades with the flimsiest claims of discrimination, undermining our entire system of learning. Furthermore, setting such a precedent might encourage professors who are afraid of giving bad grades for fear of a law suit to give good grades, even in cases where they aren’t deserved.

What, then, would be the point? College, unlike middle school soccer leagues, doesn’t offer participation trophies. The point is to prepare you for the workforce, where you must produce to your employer’s standard in order to hold a job. If everyone has a participation degree from college, how would employers know who to hire? A degree would come to mean nothing.

Does subjectiveness sometimes lead to negative consequences for students? Of course. But the alternative is worse: an everyone-gets-A’s world where going to college won’t mean anything because you don’t have to distinguish yourself while there.