Editorial Cartoonist

When the word came to the Lariat newsroom that there had been a shooting in College Station, we all had the same wide-eyed look on our faces.

It was as if everyone was simultaneously saying to themselves, “Oh no. Not this again.”

After the Aurora shooting in July and the Sikh temple shooting earlier this month, it seems like the country has gone crazy. It’s a condition that we develop whenever the country is struck by tragedy, and it only breeds more violence.

The attack on the Wisconsin Sikhs is a perfect example of this.

After 9/11, the Sikh community bore the brunt of the worst that this country has to offer.

Many Sikhs are of Indian origin, and their religion calls on people to grow their hair and beards out and wear turbans. Unfortunately this plays into that incorrect and, frankly, racist image of any Middle Easterner as the bearded, turban wearing, suicide bomber that many Americans take as fact.

Because of this they and many other groups were singled out, attacked and their businesses were vandalized all because people mistook them for Muslim extremists. Our ignorance, fear and misdirected hate made victims out of innocent American citizens, Muslim and Sikh alike.

In a way, the Oak Creek shooting was exactly what we have feared most since 9/11— an unwarranted, religious or racially motivated attack on American civilians, done at random and with no signs of remorse.

Attorney General Eric Holder labeled the attack “an act of terrorism, an act of hatred, a hate crime.”

And it was.

But unlike the picture painted by our fears, this attack wasn’t carried out by Islamic extremists or foreign-born agents of terror.

It was carried out by a white Midwesterner, a former soldier, someone like people you know in many respects. He was a musician and a community activist, and he funneled his passions into hate for people that were different.

We will probably never know why he did it, but it was fair to assume that part of the reason— like the reason for most hatred and extremism— was fear.

He might have been afraid that his way of life was changing, or that he or people he cared about were threatened by the presence of these peaceful devotees to Sikhism. Whatever the reason, it seems that he lacked the intangible quality that keeps rational people from turning into hateful, murdering, animals.

If the Oak Creek shooter had been able to respond to his fears with anything but hatred the tragedy might not have happened.

But he couldn’t. He opened fire on a group of innocents.

When things like that happen it’s easy for us to just stay afraid.

After the Columbine shooting in 1999, schools and cities everywhere started clamping down.

All of a sudden something as simple as having a mesh backpack, or blue hair, or making a poorly timed joke was seen as a sign that you were about to start shooting. Kids that may never have held a gun in their life were disciplined for pretending to. Freedom and sensibilities seemed to be cast off. It was easier to lock up students instead of providing an adequate environment for them to grow.

We were afraid. Stability, people of America, is what’s needed the most after a tragedy strikes. Level-headedness and compassion should rule the day, not fear and loathing. We the media are not helping the issue.

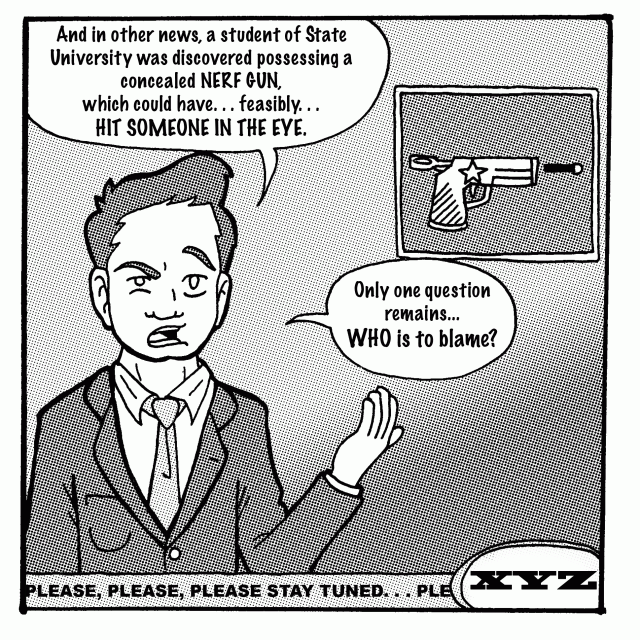

Twenty-Four hour television news stations, and vitriolic internet sites tend to blow some things out of proportion.

Continuing to go on and on about an issue can get repetitive quickly if there is no new information; thus, for the sake of entertainment, these stations can bloat news content, prohibiting the truth from reaching the public unscathed.

Furthermore, the news world is a competitive one, with each outlet trying to beat the others from print to social media.

This has led to reactive journalism instead of accurate journalism, using blocks of assumption instead of blocks of truth.

One popular way of bloating the facts to make them more attractive is adding a political attachment to the story.

For example, the Aurora gunman was prematurely identified as a member of the Colorado Tea Party, an incorrect assumption that was later retracted.

That statement caused anger across the country. The man that they incorrectly identified as the shooter spent hours as a universally hated man because of sloppy journalism.

Yes, an apology was written by the anchor online, but commentators accused ABC of a liberal media bias and some went so far as to suggest for the resignation of the anchor.

So, responding correctly will begin with us, as members of the media, doing a better job of honestly reporting— and only reporting— on what happens.

No one should ever ask us what we think about the issue, they just want to know what happened. We need to trust that Americans are bright enough to have their own opinions about events like this, and not try to tell them how to feel.

Except, obviously, in editorials and columns like this one, where we tell you our opinions whether you like it or not.

While we as members of the media take responsibility when we put illegitimate facts in your head, it’s not fully our fault when you decide to act on them.

You as individuals have the right to decide what you want to think and how to act upon it.

It is you who decides what to do after Robert Griffin III wins the Heisman: do a silent victory dance in your apartment or set a couch on fire in the middle of the street.

It is you who decides when you receive a parking ticket whether to whine about it on Facebook or actually do something about it.

And it is you who decides what to do when tragedy strikes your country: you either act out in hate, remove yourself fearfully from any aspect of the problem or you reach out to help those in need.

The choice is up to you.