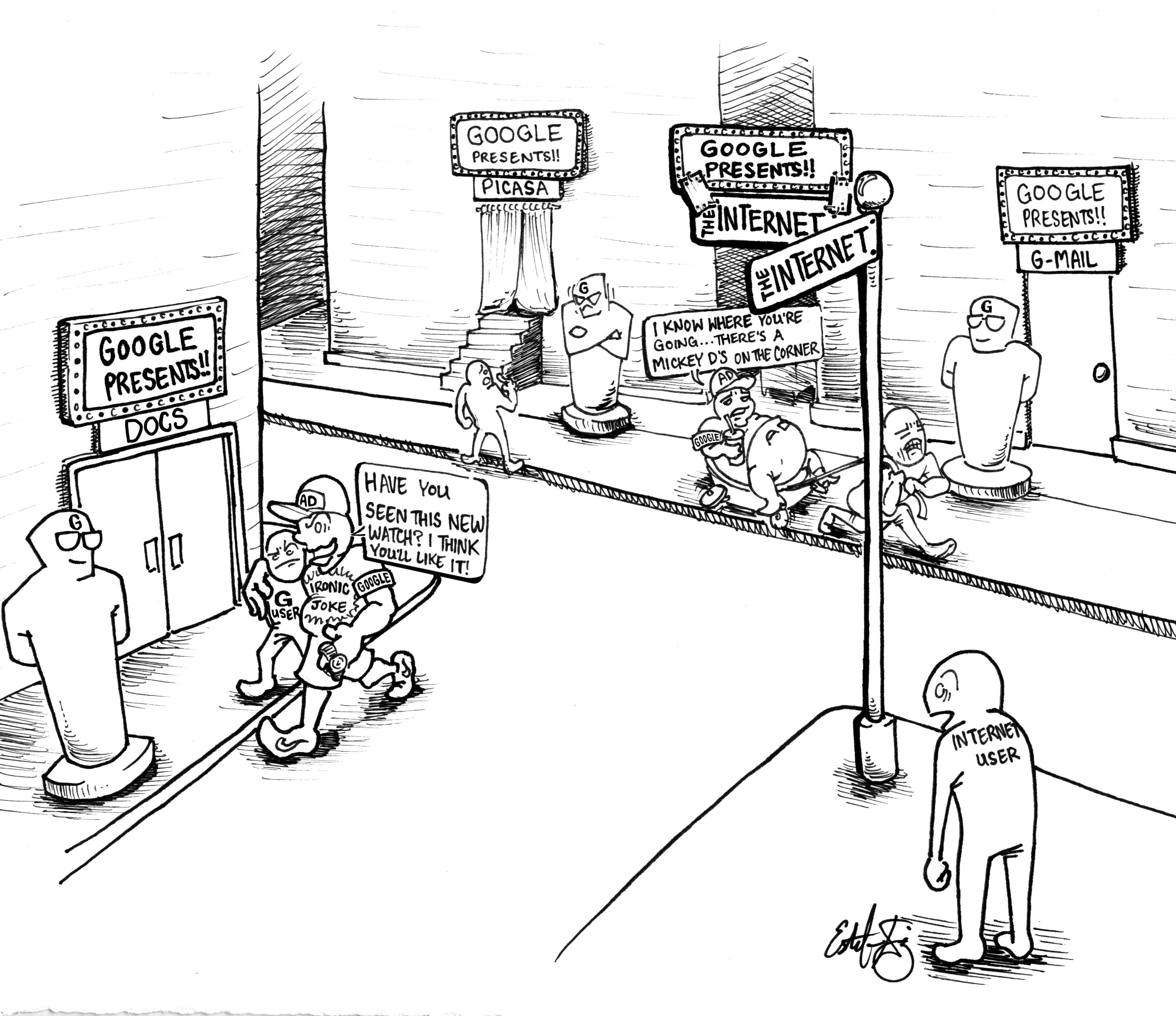

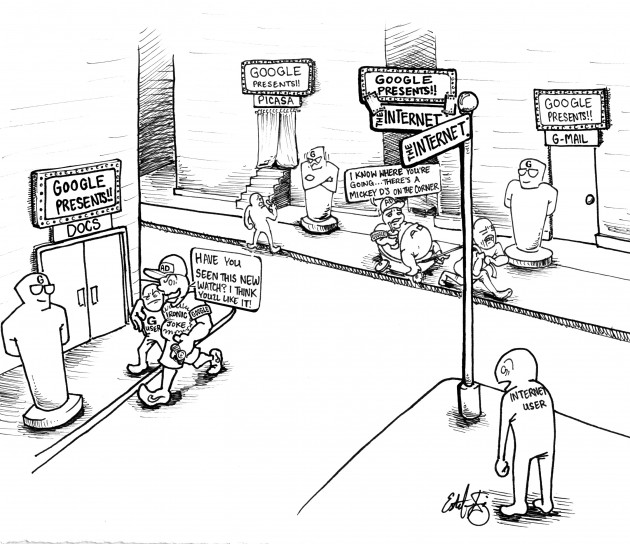

Google announced last week it will consolidate its privacy policies across more than 60 products into one universal policy.

“Our new policy covers multiple products and features, reflecting our desire to create one beautifully simple and intuitive experience across Google,” reads a description from Google.

Essentially, anyone logging into a Google account will be considered the same user on any of Google’s products, such as YouTube, Gmail or Google Plus. Browsing information will flow freely between websites, which might affect the advertisements users see and will allow Google to learn more about general demographic groups.

Google can also know where you’re located if you use a location-enabled Google service, such as Google Maps, or find your location based on the signals your phone sends to Wi-Fi access points or cell towers.

If you’re not OK with Google taking information about what websites you visit, where you live and even your cell phone location and combining that to deliver more “tailored” advertisements, you’re out of luck.

Those wanting to keep using Google products with a Google account after March 1 must accept the new privacy policy. There is no opting out of the policy.

We are discouraged by how much information Google will harvest from its users via mandate, and we think people deserve to keep their information if they wish.

The biggest argument in favor of the new policy is, “If you don’t like it, don’t use it.” This, however, misses the point.

People have enjoyed using products like Gmail, Google Docs, Calendar and Picasa, and some rely on these products to complete work-related or personal tasks. Google either created or acquired these products that users receive free of charge, and Google has grown into a multibillion-dollar company without grabbing the information it will now demand from users.

In other words, Google was doing just fine before enacting this invasive privacy policy. To suddenly demand more information from users is not only unfair but, in some cases, leaves people with no options. It is not easy or even feasible to transfer a month or two of calendar events, dozens of documents and thousands of photos to a new website just to ensure browsing information remains private.

We also understand Google is just looking out for itself, making a move it finds necessary to keep profit high and compete for advertising dollars. Facebook, perhaps Google’s greatest competition, already has access to mounds of information, and we see that reflected in the quite personalized sidebar advertisements every time we visit the site.

But when we compare the scope of the two companies, the amount of information Google now requires users to surrender far exceeds that of Facebook. Sure, Facebook can track what articles you read, videos you watch or songs you listen to, but all of that only comes with your permission.

If you want to use Facebook purely as a means for communication, and you don’t want to share your interests or link any other websites to your Facebook account, you can do that and still use all of Facebook’s features.

With Google, users either concede their entire online identity or wave goodbye to some of Google’s most useful and convenient features.

Users shouldn’t have to choose between the two. Google should realize this give users the choice to retain their information.