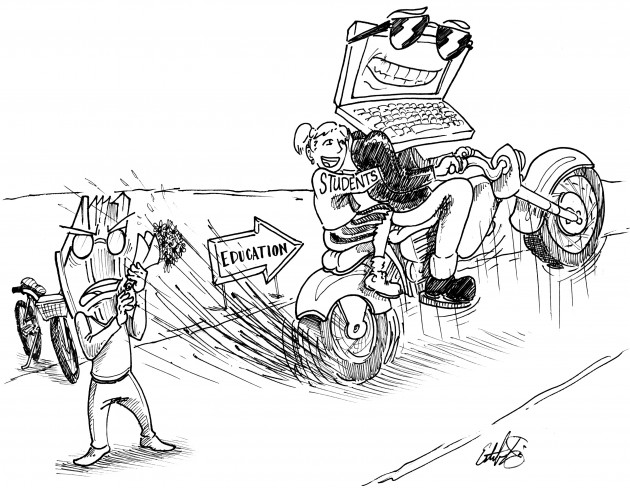

In the age of iPads, email and texting, there can be no question that the younger the generation, the more technologically savvy its members. As our culture becomes increasingly inundated by screens – TV screens, phone screens and computer screens – educators need to decide where to draw the line.

On Oct. 17 the New York Times highlighted the overhaul of schools in Munster, Ind., which spent $1.1 million to remove all math and science textbooks for its students between grades five and 12. Students now receive laptops in class to complete work and learn lessons.

The article also references a school in Mooresville, N.C., which made the change four years ago and now offers 90 percent of its curriculum online.

According to the Times article, the biggest drawback in the switch has been teachers, who have had to completely reconsider their teaching methods. Some technological glitches have occurred, but overall teachers say the technology allows them to better monitor students, who are more engaged in class.

As a safeguard, Munster schools have blocked all “noneducational Web sites, including social networks.”

From behind the wall of the opened laptop screen, however, there are plenty of diversions on a laptop that are not social network sites.

How often in class at Baylor do students spend one class period writing a paper for another or responding to emails?

If all curriculum is online, students will easily be able to multi-task during class. Furthermore, how many Internet-blocking sites are fully effective? There is often at least one child who can find a way to bypass a filter and then teach all his or her friends.

It is not just multitasking that may detract from learning. Smithsonian Magazine reports reading on a screen is a completely different experience from reading a text. Electronic reading encourages immediate participation — new ideas or unknown words can be Googled on the same device.

Maryanne Wolf, professor of child development at Tufts and author of “Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain,” argued in the New York Times that this immediate gratification will prevent young readers from learning to interact with the text. Without this skill, reading is superficial and retention stunted.

The beauty and drawback to technology is that it is constantly changing and upgrading. The middle-schoolers who are so impressed with having laptops in science class are going to lose interest after they have had those laptops for a year. Teachers will be faced with the same challenge the books presented: keeping the students engaged and present.

Even a laptop on the desk will not prevent a cell phone being used in the lap.

Within a few years, those new laptops will already be obsolete — will the school district be upgrading its technology that soon? Publishers may come out with new editions of books, but old books will still work, and they never have system outages or power failures.

The answer to the problem of education in America is not to install shiny new technology in every classroom, nor is it to bury our collective head in the sand and expect today’s youth to read “The Odyssey” before middle school.

Technology and text can be mixed. In Munster, teachers were also taught how to use Smart Boards – interactive screens that fuse computer and white board. This is the kind of technology students can appreciate – and less easily take advantage of.

If we want our students to be the successful future of America, we need to prepare them adequately: with something old and something new.