By Harry Rowe | Staff Writer

Scholars, journalists and those interested in the life of Billy Graham gathered Wednesday afternoon at Truett Seminary to attend a roundtable discussion. The talk discussed Billy Graham’s social impact and role in the removal of segregation, as well as his less desirable characteristics.

Billy Graham was a Southern Baptist minister who was mostly known for his evangelism, where he spoke to millions of people around the world as well as spiritually advising many of the United States’ presidents.

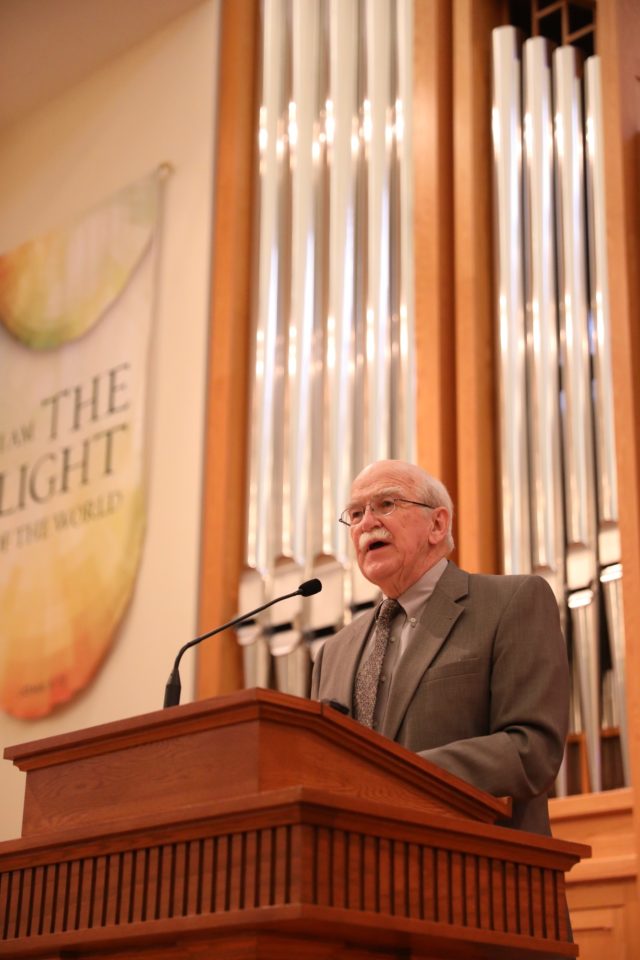

The round table discussion titled “Billy Graham and American Evangelicalism,” was part of the Billy Graham Centennial Symposium, an event commemorating the 100th anniversary of his birth. The panel, moderated by Baylor assistant professor of history Dr. Elesha Koffman, included three members: Edward Gilbreath, journalist and author; Dr. William Martin, professor at Rice University and author; and Roger Olson, Professor of Christian theology and ethics for Truett Seminary at Baylor. Each panelist, including Koffman, opened with a talk around 20 minutes related to their research on Graham and his impact on the world he so recently left.

“During my childhood, Billy Graham was always welcome in our home,” said Gilbreath, author of Reconciliation Blues: A Black Evangelical’s Inside View of White Christianity among other titles. Gilbreath, an African American, said he remembers watching lots of television in the ’70s and ’80s, but occasionally his primetime programming was interrupted to reveal a “friendly white preacher” named Billy Graham.

“As I grew older, I found myself watching his crusades. The simple yet heartfelt sermons that would culminate with the choir singing ‘Just As I Am,’ and throngs of people coming forward,” Gilbreath said. “I found myself emotionally drawn in, but I also noticed something else. Sometimes there were black people on stage with Billy Graham.”

Gilbreath talked about Howard Jones, the first African-American member of Graham’s team who arrived in 1957. He had gotten to work with him in his professional experience, and he recalled how Jones had told him that what Graham did was radical. Despite lots of angry letters from his congregation and partners who threatened to end their support if he didn’t fire him, Graham stood tall in the face of this diversity.

However, Gilbreath also talked about some Graham’s failures. He said though there was much courage in Graham’s heart, he often had a sort of timidity about him when it came to race relations. Rather than wanting to promote more social change and fight for social justice, Gilbreath said Graham believed more in personal salvation. This was evident when Graham told someone he was friendly with at the time, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., to ease the protests back for a moment and not go too fast ahead and disturb the peace, according to Gilbreath.

Martin, the Harry and Hazel Chavanne Emeritus Professor of Religion and Public Policy in the department of sociology at Rice, delivered his remarks on Graham’s influence in the White House, spanning all the way back to his meeting with Harry Truman. It was a symbiotic relationship; Graham enjoyed being in the spotlight, and the presidents enjoyed consultation for the protestant evangelical base, Martin said. He also added that Graham’s career took a permanent and devastating blow after Richard Nixon’s scandal because of how closely the two were linked.

“[Graham] fervently wanted to believe that America and Richard Nixon were involved in the work of God. Bedrock beliefs can withstand enormous challenges, but never in Graham’s life had he been forced to deal with the cognitive dissonance posed by the issue that ended Richard Nixon’s presidency.” Martin said.

Dr. Roger Olson, holder of the Foy Valentine Professor of Christian Theology and Ethics at Truett Seminary, gave his talk on Graham’s role in the church. Olson argued that Graham functioned as the unofficial pope during his leadership for the evangelical movement. From accepting Pentecostals into the evangelical movement to Graham’s endorsement of the Jesus People Movement, it didn’t get the full seal of approval from the evangelical base until Graham gave them the go ahead.

“To put it bluntly, it seems to me that for about 30 to 40 years, evangelical leaders, especially, defined their movement in reference to Billy Graham. He functioned as the figurehead leader of the movement, with such power and influence,” Olson said.

After all talks, the panelists took several questions, ranging on everything from Graham’s son Franklin and the way he has veered from his father’s path, to the current state of the evangelical movement.

Philip Jenkins, distinguished professor of history at Baylor and co-director for the Program on Historical Studies of Religion in the Institute for Studies of Religion, explained it was almost a no-brainer when choosing a place to host the event.

“We have this, and it’s a combination of a hundredth birthday and a commemoration. Baylor of course is a Christian university, it’s a Baptist university, its’s an evangelical commitment, and in a sense Billy Graham’s the founder of modern evangelicalism, he’s so critical, so our idea was, if not at Baylor, where?”