Associated Press

By Jenny Barchfield

Associated Press

RIO DE JANEIRO — When Arthur Bispo do Rosario needed art supplies within the psychiatric institution where he lived, he would barter cigarettes or trade favors with the guards. When that didn’t work, he would sometimes rough up fellow inmates and snatch away their belongings.

Bispo do Rosario, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, transformed virtually anything he could get his hands on — by any means possible — into art. And he did it for more than two decades, nearly unrecognized until the last years of his life.

A new exhibition of his works has just opened the institution where he lived: a Rio de Janeiro psychiatric institution once notorious for rampant abuses.

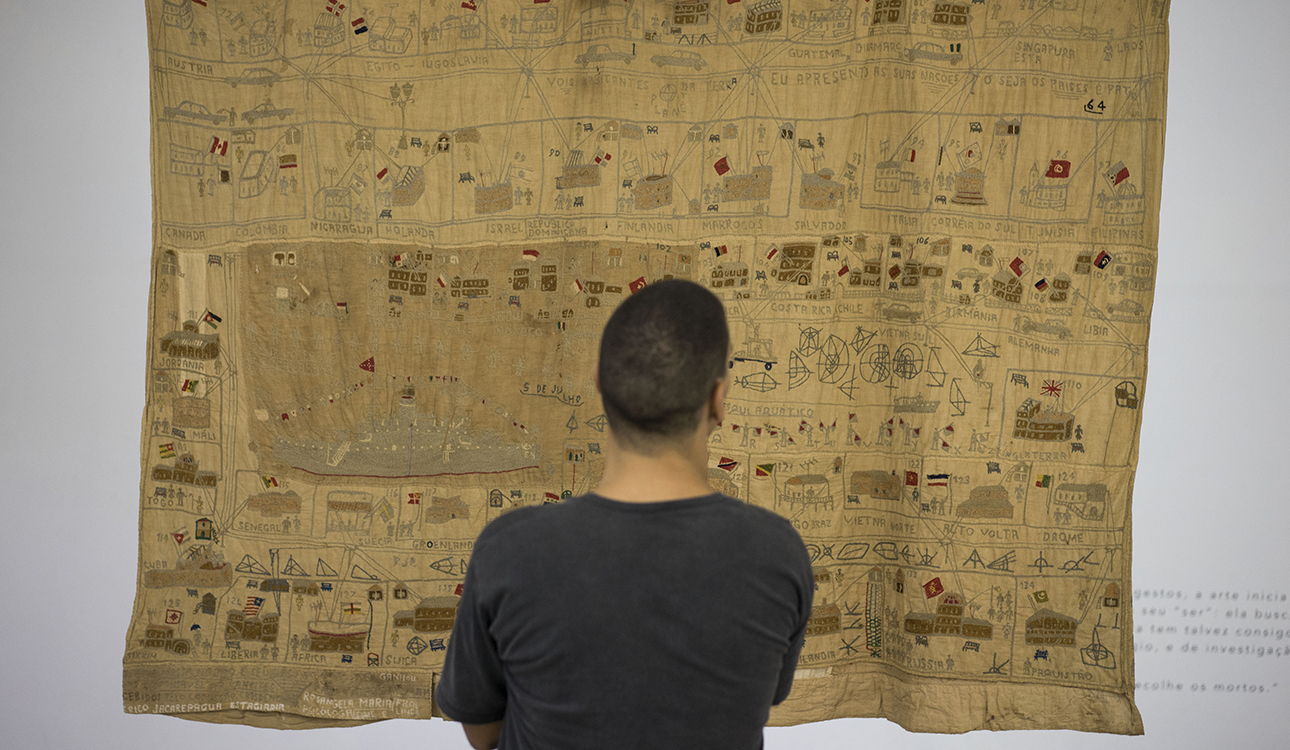

For Bispo do Rosario, the mental ward’s standard-issue blankets became wall hangings, heavy with dense scribblings of embroidery, which he made out of thread stripped from inmates’ uniforms.

His pilfered a bounty of flip flops and slippers, forks and spoons, plastic combs and other household basics that became breathtaking, surreal collages.

Wooden boxes, old vinegar bottles and used marmalade jars snatched from the trash during his periodic trips away from the institution metamorphosed into sculptures of miniature chicken coops, cars and other everyday objects he saw within the walls of his constrained world.

He even fabricated some of his own tools out of trash and found objects.

Obsessive, excessive, haunting and overwhelming, Bispo do Rosario’s work would eventually catapult him to international acclaim — even as he lived out his days within the Colonia Juliano Moreira institution.

“He used art as a way to turn confinement into freedom,” said Raquel Fernandes, director of the Bispo do Rosario Museum of Contemporary Art, adding that Bispo do Rosario is widely considered one of Brazil’s five most important contemporary artists. His work has twice been featured at the Venice Biennale.

More than 100 of Bispo do Rosario’s 800-plus works are on display at the museum, which is tucked inside the grounds of the sprawling Colonia where more than 5,000 patients were once locked away under often-horrific conditions.

A 1980 television expose on the institution led to its gradual phase-out, with most patients being sent back to their families or to other institutions, although around 300 mostly geriatric patients still live on the premises. Bispo do Rosario died there in 1989.

The son of a carpenter, Bispo do Rosario was born in 1909 in the remote, northeastern town of Japaratuba. Little is known about his childhood, but an official register shows him joining a Naval training academy in 1925.

After moving to Rio, he enlisted in the Navy and served for nine years, while capitalizing on his imposing physique to pursue a career in boxing.

In 1938, he had the first of what he would describe as “revelations,” mystical apparitions that psychiatrists would later diagnose as acute schizophrenic episodes.

A stint in a Rio de Janeiro mental hospital was the first of several, culminating in his 1964-1989 stay at the Colonia Juliano Moreira.

“He came to accept this was his place,” said director Fernandes, adding that the artist gradually filled the ward with his mushrooming art collection. “He turned it into his gallery, his atelier and his archive all at once.”

Visitors to the Colonia, which has seen much of its grounds swallowed up by encroaching slums over the past decades, can still see the cell where Bispo de Rosario spent seven years in near-solitary confinement of his own volition. In a dank corner of a crumbling hall that once housed the most agitated patients, the tiny cell is illuminated by two small windows fitted with iron bars.

Inside solitary he had another revelation: Voices told him his mission was to catalog all things on earth ahead of judgment day. Hence the sculptures of everyday objects — a slingshot, pliers, a mousetrap, a paint roller, a machete — entirely swathed in embroidery.

“He didn’t accept medication, didn’t participate in the art therapy workshops, really kept to himself,” said Fernandes. “But all that time, he was creating, just creating.”

Museum visitor Elton Ribiero said he was impressed by the transformative power on display in the exhibit.

“We know what the mental wards in Brazil were like at that time. There was so much violence, so much suffering,” said Ribeiro, a 30-year-old psychologist. His work “was the way he found for him to live in all that.”