The Supreme Court began hearing oral arguments this week for a case that will ultimately determine whether a university or the creator should hold the patent of a federally funded invention.

The case, Stanford v. Roche, is based on a disagreement between Stanford University and a California biotechnology company called Cetus, which later sold its assets to a pharmaceutical company known as Roche Molecular Systems Inc. In 1989, Stanford AIDS researcher Mark Holodniy signed a consulting agreement with Cetus, which gave the company rights to any invention Holodniy created from his access to the company’s resources.

Although he was consulting at Cetus, Holodniy was still researching under contract for Stanford, so the university filed for a patent on Holodniy’s invention, which monitors the effectiveness of an anti-HIV treatment. Stanford filed the patent under the Bayh-Dole Act, which was developed to encourage technology transfer – a form of knowledge transfer – that would allow wider distribution and faster development of important scientific findings in order to benefit the greater public. In 2000, Stanford began asking Roche Molecular Systems Inc. to pay the university for a license since the pharmaceutical company was selling medical kits that test the effectiveness of anti-HIV therapy, which Stanford claimed was a patent infringement on Holodniy’s invention.

After failed licensing negotiations between the two institutions, Stanford filed a lawsuit against Roche Molecular Systems for patent infringement.

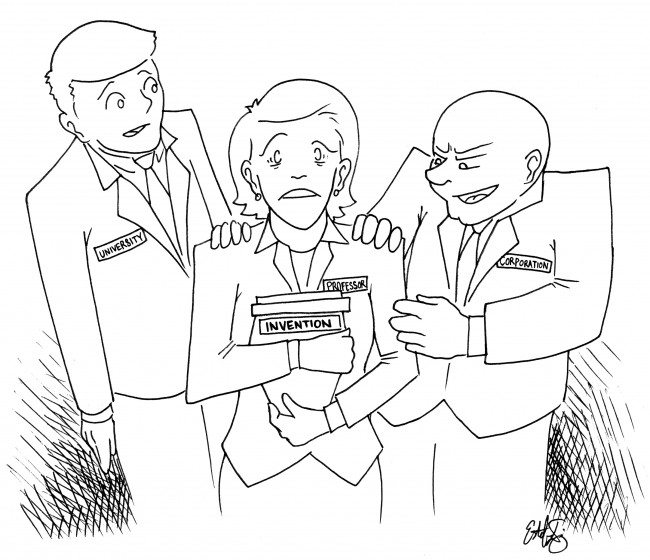

Several court hearings followed this original lawsuit. Now the Supreme Court has to make a final decision: Should the university hold the patent of an inventor under the Bayh-Dole Act, or should the faculty researcher retain the rights to his or her own invention? Both sides have compelling arguments. A university-controlled patent would allow the public to benefit faster from the invention through technology transfer, as the university would be able to partner with companies to further develop the new invention for the marketplace.

But as the creator, it would seem natural that the faculty researcher should retain the rights to his creation in order to determine where his research is to be used and to what ends. In both situations, the researcher would receive federal funding and at least a portion of the invention’s royalties, which leaves technology transfer as the determining issue.

As defined by “Science and Engineering Indicators,” a publication of quantitative information by the National Science Board, technology transfer is an “exchange or sharing of knowledge, skills, processes, or technologies across different organizations.”

This transfer between universities and corporations offers an opportunity to further develop and expand the invention, a growth that would be nearly impossible for the individual researcher who would not normally have a wide reach to other companies and universities.

The development of new inventions would also allow for the invention to rapidly reach the marketplace and ultimately better serve the general public. Considering the immeasurable advantages of some inventions, such as Holodniy’s technique for measuring anti-HIV treatment, the transfer of knowledge is one of the greatest benefits to society as well as to the researcher, who has the gratification of seeing his doubtless well-intentioned research used for the greater good.

Therefore, we believe the university should file and earn the patent for all federally funded faculty research so that the inventions and creations developed from the research may be made fully ready and accessible to the public.

While we also believe the researcher should retain a portion of the invention’s revenue as well as maintain the name of inventor, his invention would be made better through technology transfer and be able to more swiftly impact the future of society.