Carlye Thornton | Lariat Photo Editor

By Viola Zhou

Reporter

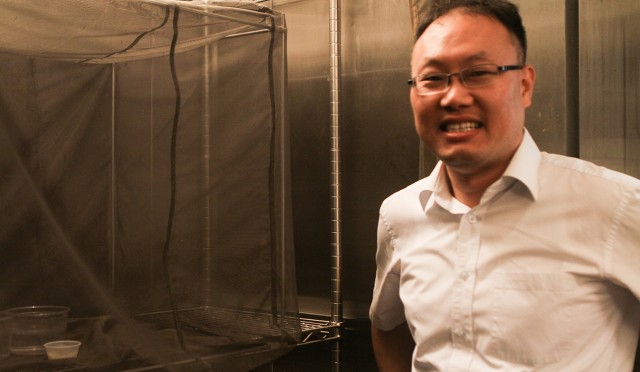

Dr. Cheolho Sim, assistant professor of biology, has a laboratory that is as dark, hot and humid as a rainforest. He keeps various species of mosquitoes there and works on ways to prevent them from spreading tropical diseases.

He is one of several Baylor scientists in the battle to eliminate mosquito-transmitted diseases, which in developing countries claim millions of lives every year.

“Billions of people living in the developing countries live on less than $1 per day,” Sim said. “They live in homes without any windows. Mosquitoes can go in and out.”

Sim said he is developing a transmission-blocking vaccine for lymphatic filariasis, a disease transmitted by mosquitoes common in Africa and Southeast Asia. It is commonly known as elephantiasis, because people who are infected develop swelling legs and arms.

Sim said the vaccine will be used for both healthy and infected people. When mosquitoes bite them, a certain protein in the blood will enter their bodies and induce a process to kill the parasites.

He said the vaccine cannot cure the patients, but it can stop the parasites from reaching the next person. He is also studying how to suppress mosquito populations in the field.

Dr. Chris Kearney, associate professor of biology, is looking to plants to stop mosquitoes from carrying parasites around.

“Male mosquitoes use solely nectar for their nutrition,” he said. “If we can have a protein toxic to mosquitoes that could be expressed to nectar, that would be a way of killing male mosquitoes.”

Kearney said after screening many candidate plants, he found impatiens the best vehicle for the toxic proteins. They has high amounts of nectar and protein. They is also easy to grow and can be genetically modified.

“Now we have the plant that the mosquitoes are very happy with,” he said. “Now we can work on the machinery of putting that toxin gene in and get it expressed.”

Kearney said his team has isolated the protein produced in the nectar and worked out its gene sequence. He will try to replace the protein gene with a toxic gene and put it back into the plant.

Kearney said toxic bite nets and indoor sprays have been successful in lowering mosquito population in many areas, but mosquitoes adapt to these method by moving outdoors. New ways of controlling them are needed.

Sim said the biology department is developing a new tropical diseases track for undergraduates in collaboration with the Baylor College of Medicine. It will prepare students to work on research and health care related to these diseases.

Although the tropical diseases have a significant impact in the Third World, Sim said their research is not getting enough funding in the United States because the problem seems far away.

“I think we only worry about ourselves for the most part,” Kearney said. “Very few people in America know what dengue is. It is the worst mosquito-borne disease in the Americas. We don’t even know about it. But when it moves northward, we will.”

Kearney said the threats are getting closer.

“With global warming, southern parts of United States are tropical now,” he said. “South Florida and South Texas are the next places where you can have diseases move in.”

Sim said the spread of Ebola reminds people that problems in the developing countries can become their own.

“Ebola is one of the tropical diseases, and was not familiar with people in the United States,” Sim said. “But it’s not their issue. It affects the entire globe. That brings us some new signals. If we cannot help them, it can be our issue anytime.”