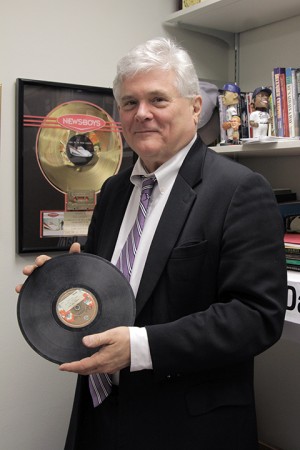

Travis Taylor | Lariat Photo Editor

By Ian Currie

Reporter

A Baylor associate professor’s collection of Black gospel music will be permanently featured in the new Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture in 2015.

Robert Darden, associate professor in the department of journalism, public relations and new media, sat down with the Lariat to discuss his attempt to preserve this aspect of American culture and the relevance of black gospel music in today’s world.

Q: What is the Royce-Darden Collection?

A: To try and tell a long story in a short fashion, African-American sacred music has been my passion since I was a child. I was gospel music editor for Billboard magazine in New York for 12 years. I moved on to freelance writing.

Then I got an opportunity to write books for tenure. I wrote the book “People Get Ready! A New History of Black Gospel Music” for academic merit, rather than for sale.

In researching the book I discovered that 75 percent of the black gospel music from 1940-1970, which is known as the “Golden Age,” was all unavailable to the public.

Q: What was the next step in initiating the collection?

A: I wrote an editorial, which The New York Times ran, bemoaning the situation with the music. I was angry.

If we allow this music to be lost forever then future generations will judge us harshly.

Charles Royce, a businessman, called me and told me that if I could come up with a plan to save the music that was being lost, he would pay for it.

Myself and staff at the Moody Memorial Library came up with the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project. It would need $350,000, which Royce paid for.

Q: How does the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project work?

A: We identify, acquire, digitize, catalog and eventually make black gospel music accessible.

We have a state-of-the-art studio in the basement library. Once people heard about the project, they started sending in their vinyls.

Q: How do you evaluate which music fits the category for the project?

A: I’m not interested in quality judgment. If it meets the dates, I don’t care about the quality.

As long as it is gospel. It doesn’t have to be written by a black writer, or sung by a black singer.

If Kanye West writes a gospel song, does the fact that he is writing it make it not gospel?

Does he live a pure and holy life? No, but lots of black gospel artists wouldn’t claim that kind of life either. That isn’t my business.

I believe I have been called to save this music. Let others catalog it.

Q: How did this music come to be “lost,” in your words?

A: Firstly, this music was released in the most racist period in American history. It was not valued by people, and the vinyls were sold for scrap.

African-Americans had their music stolen from them as they had no ability for legal recourse.

However, even among many African-Americans, gospel was viewed as embarrassing or undignified and was not regarded as highly as jazz or blues.

Additionally, it had an exceptionally poor audience. A small, independent label would have a big hit. Then a white company would swoop in and sign the artist, only to release them a few songs later. The original label would be financially unsustainable and out of business.

Q: You have said that we are still in a civil rights movement. What do you mean by that?

A: African-Americans still earn less money doing the same jobs as others. They are under-represented in virtually every state. It seems that the spasms of racism across our country occur almost weekly. I continue to see racism in Waco and my travels to the Deep South.

The opportunities for African-Americans continue to lag behind those of whites. A higher percentage of African-Americans are in jail for the same crimes white people commit, they die younger, and their children die younger.

This is a problem that exists throughout the Western world. As a result, the music will not die.

Q: Therefore, gospel music is still relevant?

A: The civil rights movement will resurrect and this music will rise to the forefront as it is needed – as it always has.

Egypt, China, Syria, in all these struggles people have banners that can be translated to read “We shall overcome.” There is power there. My job is to quantify that power, both as an academic and as a fan.

Q: So black gospel music has a significant role to play in the movement for civil equality?

A: Yes. During and up to the 1960s African-Americans controlled little of the media.

There were few black newspapers, few black authors were published.

Through all of this music continued to percolate. Right under the people that oppressed them a great culture of artistic creation that continues with recent music.

The information contained on obscure LPs gives a unique window to the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s where African-Americans had very few other avenues of expression.

We are saving a piece of African-American history and it helps us understand how we got here from there. What’s not to like?

Q: How will people be able to access the music at the Smithsonian?

A: The black gospel section will be a part of the store in some way. We provide music to them, and they figure out the technology to make it accessible to people, in the same way that it was accessible to their grandparents.

Q: What is the date for the completion of the museum?

A: As far as I know, and they’re working all these things out simultaneously, they are aiming for early 2015.

I hope to be able to see it open. But we have no idea how much we have saved, or how much we have lost.

Q: But it is a start?

A: Yes. There is no database for this music. We have 8,500 sides cataloged as of a week ago. I couldn’t give you a number of songs.

It is a start. I have two dreams: to save it and make it accessible to everyone.

I get to play my research on my car radio on my way home.

What’s not to like?

Travis Taylor | Lariat Photo Editor