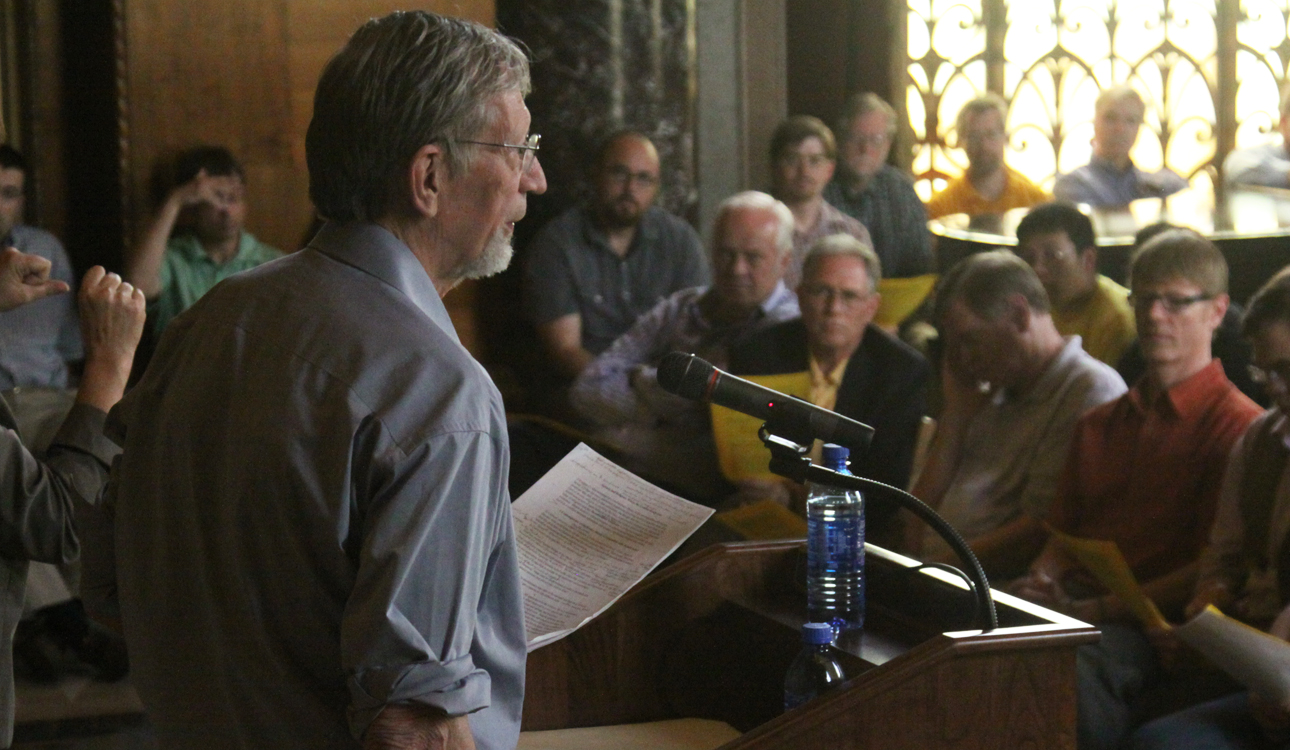

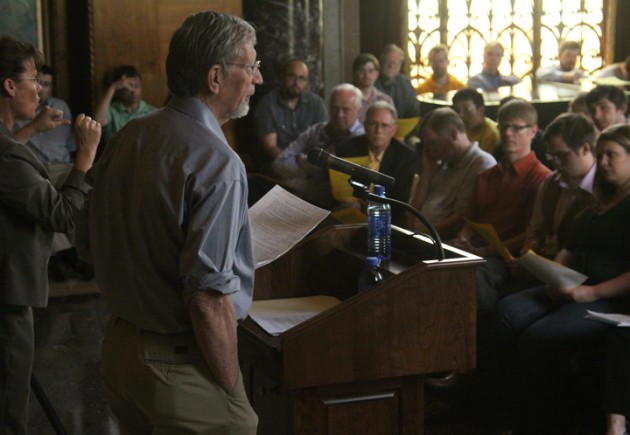

Chris Derrett | Lariat Editor-in-Chief

By Daniel C. Houston

Staff Writer

One of the country’s most prominent philosophers claimed Thursday it is science and naturalism — not science and religion — that conflict with one another in front of a packed room of Baylor students and faculty.

Dr. Alvin Plantinga, professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, said some atheist intellectuals like Richard Dawkins argue Christianity is fundamentally incompatible with the theory of evolution, and many Christians buy into this notion, because they believe evolution requires species adaptation be considered “unguided.”

Plantinga, however, said these critics of Christianity fail to prove the evolutionary process couldn’t be guided according to a particular design.

He went on to argue that believing both in a world in which all actions are determined by material biology, as well as in the theory of evolution, is irrational.

“Naturalism is, in fact, a kind of religion, and if it’s incompatible with evolution, then it’s incompatible with science,” Plantinga said. “So I agree that science and religion — or science and quasi-religion — conflict, all right, but it’s a conflict between naturalism and science, and not a conflict between Christianity or theism and science.”

To defend the claim that naturalism conflicts with evolutionary theory, Plantinga said a person who believes in both naturalism and evolution has reason to believe human cognition itself is not reliable.

This, he said, would undermine a person’s ability to believe his or her mind comes to true conclusions more often than not, which would also undermine the original belief of the compatibility of naturalism and evolution. Thus, Plantinga concluded, the belief in naturalism and evolution is self-defeating.

Not all audience members thought his argument was convincing. Several students, including Miami senior Alan Swindoll, raised objections to Plantinga’s arguments during a question-and-answer period following his lecture.

“I agree with him personally, but this is the main thing that [critics] talk about,” Swindoll told the Lariat after the event. “Why should we believe that these natural creatures wouldn’t have true beliefs? I was trying to point out that if you have true beliefs, that might help you in a natural environment. But he’s saying that doesn’t have anything to do with it because natural selection only cares about behavior, [not beliefs].”

Swindoll said he thought Plantinga responded convincingly to his objection.

Other audience members questioned whether it really was irrational to hold a belief solely because that belief is improbable.

Dr. Trent Dougherty, professor of religion at Baylor, introduced Plantinga and said his defense of theism in the academic world has helped make it acceptable to be a Christian philosopher in academia, something that was not always taken for granted.

“What it is like for me to be a Christian philosopher when I came up through grad school [in the 2000s] is different because of the efforts of this man in his early career, forging a path that people like me were later privileged to walk,” Dougherty said.