Last week, ESPN.com reported Iowa Hawkeyes football player Willie Lowe requested a release from the team.

After unintentionally losing 20 pounds since January and suffering from headaches in that time, finding a new school could be the least of Lowe’s concerns.

Lowe is not sure he’ll ever be able to recover from a muscle disorder, rhabdomyolysis (rab-dough-my-all-low-sis), which was discovered in January and caused his symptoms. While his situation is worse than those of some of his teammates, he is still one of 13 Iowa players hospitalized at one point from the same cause.

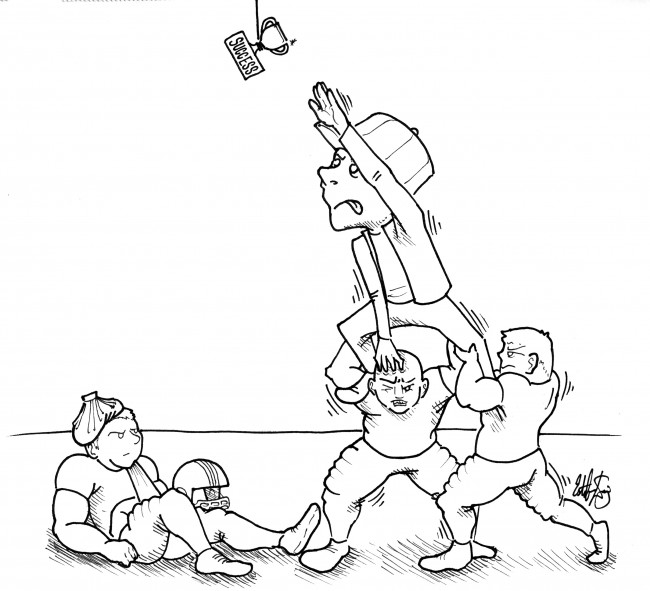

The National Strength and Conditioning Association said a workout, forced on the players for offseason conditioning and blamed for the disorder, was misused. Players said part of the exercise in question included 100 timed weight-lifting squats.

“This workout is not a common workout and has no scientific basis to be used to train college athletes,” Jay Hoffman, president of the board for the NSCA, told USA Today.

Iowa later agreed to remove the workout from its training regimen.

Unfortunately for Lowe, the damage has already been done. From here, all Iowa and other athletic programs can do is learn from a painful lesson. At no point should player safety take a backseat to pursuit of success.

There is no excuse, especially at the highest level of collegiate athletics (Division I), for coaches and training staffs not knowing the limitations of their athletes in workouts.

Every player has different capabilities, but if 13 players are pushed to the point of extreme muscle breakdown from the same exercise, the staff has failed.

Aside from being logically unwise, creating an atmosphere in which athletes cannot feel secure about their well-being causes poor morale as well. A Facebook post from one of Iowa’s injured players, for example, read, “I had to squat 240 pounds 100 times and it was timed. I can’t walk and I fell down the stairs … lifes [sic] great.”

Football has and always will be a game stressing physical and mental toughness. A coach’s ability to keep players focused, even intimidated, can immensely help a team’s success.

Even so, the game has evolved, as has every sport. In the midst of preseason practices last August, coach Art Briles was asked to compare training methods when he was a player in the mid-1970s to today’s training, which often involves heavily calculated workouts and diets.

“We’re a lot smarter now,” Briles said. “I don’t know how we survived back then.”

Toughness cannot be confused with foolishness. When athletes and coaches look back on this generation of athletics, they should not have to question how injuries were avoided in training.

Iowa has and will continue to move forward from this mistake. Lowe did add that for most of the hospitalized players, the rhabdomyolysis symptoms have decreased, and most of those affected are recovering well.

But even one player is too many when it comes to taking unnecessary risks with poorly researched exercises.