By Julia Vergara | Staff Writer

The number of liquor law violations at Baylor increased over the past two years, according to the 2017 Annual Safety and Security Report. There has been a 39.5 percent increase in the number of people arrested for campus liquor law violations from 2015 and a 76 percent increase from 2014.

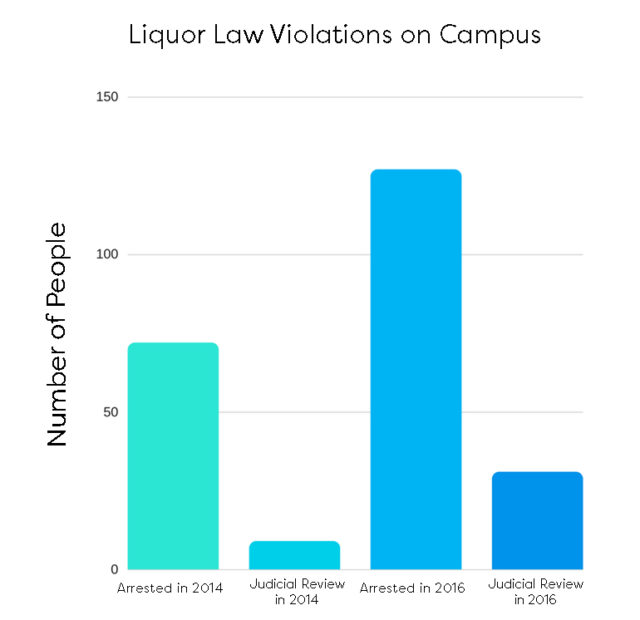

In 2014, 72 people were arrested and nine people received a judicial referral for on campus liquor law violations. In 2015, 91 people were arrested and 11 people received a judicial referral. In 2016, those numbers had increased to 127 arrests and 31 judicial referrals.

The Baylor University alcohol and drug policy states that it is a violation for anyone to possess, use or be under the influence of an alcoholic beverage on campus or at a university-related activity off campus. A violation of this policy results in disciplinary action which can range from a warning to expulsion.

According to Judicial Affairs website, alcohol violations accounted for 37 percent of all misconduct violations adjudicated by Judicial Affairs and 77 percent of disciplinary suspensions were alcohol or drug related for the 2015-2016 academic school year.

Senior Coordinator for Recovery Services Lilly Ettinger said that she believes more consistent enforcement and a larger student population have affected the increase in liquor law violations in 2016.

Despite last year’s increase, alcohol use has actually been decreasing in popularity for a long time, Ettinger said.

“Alcohol and drug use on the overall have declined for the last twenty years,” Ettinger said. “Most students at Baylor don’t drink.”

According to Judicial Affairs statistics, the 2002-2003 school year had a total of 311 alcohol violations and numbers have not reached that high since.

However, alcohol still poses a threat on college students’ lives.

One in four college students reports an academic consequence from drinking, Ettinger said. The academic consequences can include anything from skipping class to lower grades or doing poorly on exams.

The worst consequences involve death and assault. Ettinger said that a little over 1,800 college students aged 18 to 24 die each year due to unintentional alcohol-related injuries and almost 700,000 assaults between students 18 to 24 involve alcohol.

“Alcohol use shouldn’t define the college experience,” Ettinger said. “And it’s normal not to drink. I wish everyone knew that it’s normal not to drink.”

While the 2017 Annual Safety and Security Report shows an increase in liquor law violations, many other offenses have shown a decrease in 2016, with the exception of arson and dating violence.

In accordance with the Clery Act, all colleges and universities receiving federal funding are required to publish and distribute campus safety and security policies and crime statistics for the previous year by Oct. 1.

Clery Compliance Manager Shelley Deats said her job involves a deeper analysis of crime reports, coming from places such as the Baylor University Police Department, Title IX or Campus Security Authorities, to ensure that Baylor gives the community the most accurate numbers.

“We will take a report and dissect it and just ensure that we’re not overcounting or undercounting,” Deats said. “That way when people come in and take a look at those charts and those numbers, they can have the utmost confidence that we’ve really thoroughly gone through what needs to be in there and what doesn’t.”

Deats said that the difference between police crime reporting versus Clery crime reporting is that the police deal with incidents that they have investigated and that have proven to be a case whereas Clery crimes are reports of alleged crimes — so they may or may not have occurred.

Baylor sent out their report in an email on Oct. 1 that said, “In compliance with federal law, the following is sent annually to all students, faculty, and staff. This notice contains information that the University is legally required to convey to you; you are strongly encouraged to read it.”