When Chief Justice Cody Coll delivered an order of no contact to the Lariat on Thursday, there was some confusion. We had never heard of a no-contact order being issued to the Lariat — or any press for that matter — before. The order states that “No member of the press shall make intentional contact with any member of the Court regarding [McCahill, Hardy v. Kinghorn] EXCEPT the Chief Justice of the Court, Cody Coll, who shall serve as the SOLE SPOKSPERSON [sic] FOR THE COURT.”

The court decided to hear McCahill, Hardy v. Kinghorn last week. Two student senators, Woodinville, Wash., senior Gannon McCahill and San Antonio junior Chase Hardy, filed the lawsuit against Katy junior Lawren Kinghorn, internal vice president. According to the lawsuit, McCahill and Hardy are suing Kinghorn because she demonstrates a disregard for rules outlined in the student government bylaws.

The document Coll hand-delivered to the Lariat newsroom was an order to not contact anyone on the court other than Coll. If any member of the Lariat contacts someone other than Coll on the court, the court will hold that person in contempt of court and refer him or her to Judicial Affairs for further action or discipline. This document was amended Monday night and sent to Lariat editor-in-chief Linda Wilkins, Tyrone, Ga., senior, by email at 9:20 p.m.

The amendment clarified that no member of the press “who is subject to the jurisdiction of the Court” can make intentional contact with any justice other than Coll regarding the case.

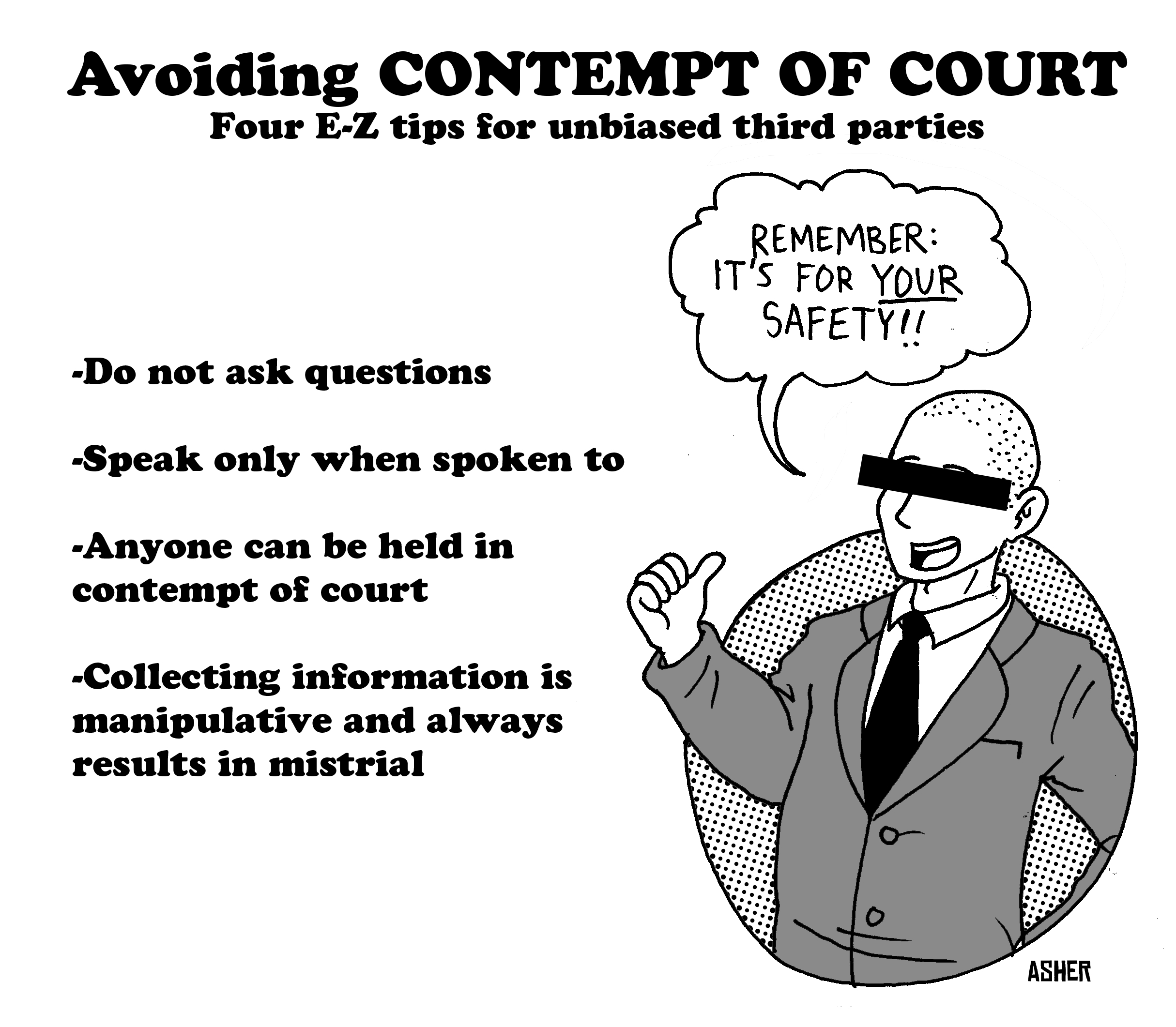

Coll told the Lariat the order protects the integrity of the court as well as the student newspaper. He said the Lariat could introduce bias to the justices through questions in an interview. If this happens, and if the case ends in a mistrial, the court could hold members of the Lariat in contempt of court.

At first glance, it may not seem like this order is a big deal. It is, however, quite the contrary.

According to the Student Body Constitution, which can be found online, the Student Court has the “power to issue charges, subpoena, [sic] and orders.” The constitution also states that any student who fails to comply with a decision of the court will be in violation of a disciplinary policy of Baylor.

From these statements, the court has the power to issue orders to students at Baylor. Coll said Friday that because the Lariat staff is made up of students, the court has jurisdiction over Lariat staff members and can issue them orders.

However — and this is a big however — the order was issued in regard to one particular case, a case with which the Lariat was not and still is not involved. According to the Student Body Constitution, the court’s jurisdiction extends to conflicts arising between students v. organizations, students v. students and organizations v. organizations. There was no dispute between the Lariat, the justices or the parties involved in McCahill, Hardy v. Kinghorn at the time the order was issued.

Serving an order to a non-party is outside of the court’s jurisdiction, especially considering the threat of being held in contempt of court. The fact that the order was deemed necessary to protect the Lariat is, well, questionable. It is difficult to hold a non-party liable for bias among the court justices, who have the option to decline an interview.

Beyond this, the original order is directed at members of the press — explicitly stated in section 2 of the order. The court has jurisdiction over students — that’s true to a point. But over all members of the press? The amendment does clarify that this order is not directed toward all members of the press — only those who happen to be students at Baylor.

The Lariat is a laboratory for students who want to learn and gain experience in journalism. Our job as journalists is to report every story as completely as we can. That means contacting as many sources and asking as many questions as possible in order to cover every angle of a story. Sources have the right to decline an interview. To order the press not to contact a potential source places a restriction on our ability to report as fully and as comprehensively as we can.

Ultimately, restricting the press is unconstitutional. The First Amendment of the United States Constitution reads, “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” The Supreme Court does not create laws — that falls under Congress’ responsibilities. However, the Supreme Court does interpret and apply the laws. If any law conflicts with the constitution, the Supreme Court can strike it down. The Supreme Court has the right to issue gag orders to parties involved in a case or dispute.

Gag orders direct parties in a case not to speak to the press. The press can still contact these parties. However, the Supreme Court does not issue orders to prevent the press from contacting parties in a dispute. Why? It would conflict with the press’s freedom to report stories. It hinders the reporting process and, by default, the ability of the press to print.

When the press is restricted, the general public is less informed. The press provides a service to society. It acts as a watchdog for the people. It brings clarity to complicated stories. It gives information to people about their surrounding communities. Without being able to fully research, journalists are suppressed. When journalists are suppressed, the people are too.

Although we are students, we are members of the press. As such, we choose to uphold the our constitutional rights. We will abide by the rules outlined for student publications in the Baylor’s Student Body Constitution.

But we will not submit to an order that impedes our ability to do our jobs as members of a free press.