Freedom of religion is again at the forefront of a Supreme Court case. On Nov. 6, justices heard oral arguments in Town of Greece v. Galloway, No. 12-696.

Freedom of religion is again at the forefront of a Supreme Court case. On Nov. 6, justices heard oral arguments in Town of Greece v. Galloway, No. 12-696.

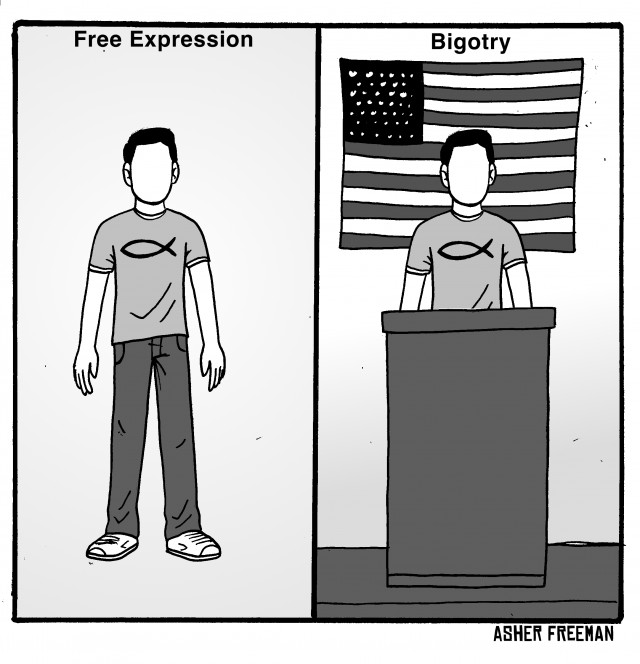

Two residents, Susan Galloway and Linda Stephens, in the town of Greece, N.Y., a suburb of Rochester, filed a lawsuit against the town complaining that they and other residents that attend council meetings are a captive audience because the council opens every meeting in prayer. They contend that because nearly every prayer offered in an 11-year span were overtly Christian, that the town was endorsing Christianity, which is viewed as a violation of the First Amendment’s establishment clause.

The trial court ruled in favor of the town while the appellate court ruled in favor of the plaintiff.

However, the town has expressed willingness to have prayers offered by non-Christians to start its council sessions, as evidenced by the prayers offered by a Jewish layman, a Wiccan priestess and the chairman of the local Baha’i congregation during 2008. It has expressed that members of all faiths and atheists are welcome to give the opening invocation.

The fact that the town of Greece is open to prayers offered by members of all faiths, not just Christianity, shows that they are not engaging in the establishment of religion.

We believe that the Supreme Court should rule in favor of the town, otherwise they will be infringing on the free-exercise rights of not only the person that offers the prayer, regardless of their religious belief, but also of those that support the concept of opening the council meetings in a prayer.

Justices engaged in a give-and-take throughout the oral arguments. Justice Elena Kagan summed up the difficulties that the Supreme Court faces when she stated, “Every time the court gets involved, things get worse instead of better.”

Justice Anthony Kennedy stated his opposition to the idea of government officials or judges examining the content of prayers for sectarian phrases or content because “that involves the state very heavily in the censorship of prayers.”

Throughout the arguments, Justice Stephen Breyer was trying out potential outcomes that not only recognized the rights of those in the religious minority as well as non-believers but also recognizes the tradition of prayer.

The Supreme Court previously ruled in 1983 in Marsh v. Chambers that prayers in the Nebraska Legislature did not violate the First Amendment.

At the heart of the issue is two seemingly contradictory clauses found in the First Amendment in relation to the role between government and religion. The first is known as the establishment clause, which reads “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

This clause was designed to prevent the federal government from establishing an official religion, something that was common in other countries, including the one that the United States fought against for our independence.

The clause has also been expanded to prohibit the government from unduly preferring one religion over another, unduly preferring religion over non-religion or unduly preferring non-religion over religion.

The other clause at issue is the free-exercise clause in the First Amendment. The free-exercise clause reads “or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This clause was designed to allow citizens to accept any religious belief or engage in any religious rituals that they choose.

It also protects actions done based on those beliefs. It is important to note that the courts have placed some limits on the exercise of religion, despite the fact that the clause is an absolute. This clause has been interpreted by the courts as the freedom to believe is absolute, however the actions based on those beliefs is not absolute.

Both the establishment and free-exercise clauses, as originally intended, were only to apply to Congress and the federal government. In 1940, the Supreme Court in Cantwell v. Connecticut held that the free-exercise clause is able to be enforced on state and local governments.

In 1947, the Supreme Court, in Everson v. Board of Education, held that the establishment clause is one of “liberties” that is protected by the due-process clause in the 14th Amendment. It was at that point that the establishment clause was made to be applicable to all levels of government from the local level all the way through to the state and federal level, which was a huge expansion of the applicability of the establishment clause.

Many people, including the courts, view that these two clauses are contradictory.

Depending on one’s viewpoint, the government taking one action would violate the establishment clause but its failure to take action would be in violation of the free-exercise clause.

The University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law in its Exploring Constitutional Conflicts website uses the example of the government providing or not providing military chaplains to troops stationed overseas.

Some people would view the government’s provision of military chaplains as a violation of the establishment clause.

However, others would view the government’s failure to provide military chaplains as a violation of the free-exercise clause.

We call all Americans to be like Samuel Adams who, when the Continental Congress was considering having a prayer recited at the first session, said, “I hope I am no bigot, and can hear a prayer from a gentleman of piety and virtue who is a friend to his country.”

As long as the person that is presenting the prayer is pious and virtuous as well as a friend to the United States, everyone should be able to hear a prayer given by that person, regardless of whether the prayer is by a Christian and offered to God, by a Muslim and offered to Allah, by a Wiccan and offered to Apollo and Athena, or by a person of any other religion offered to their god.