From left to right- Stuart Smith, Claire Kultgen, Noelle Smith, Stacy Wren and Ross VanDyke. Seen here shortly before starting for the summit.

By Rob Bradfield

Editor-In-Chief

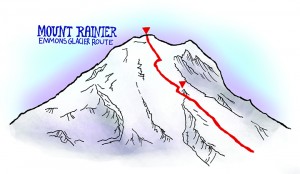

On June 19, 2012 five climbers from Waco set out to summit Mount Rainier, the highest peak in Washington’s Cascade range.

Rainier, popular with outdoor adventurers, climbs 14,411 feet above the Pacific Ocean. On a clear day it can be seen from Portland to the Canadian border.

The group included Stuart Smith, a Waco attorney with a climbing resume that includes some of the world’s tallest peaks — including Mount Everest, and Ross VanDyke, Baylor’s Assistant Director of Admission Counseling who had made a previous attempt on Mount Rainier that was called off due to weather. Joining them were Smith’s niece Noelle Smith, Claire Kultgen, and Baylor senior Stacy Wren, from Waco.

The climbers were using Rainier as a warm up for trips to Mount Denali, the tallest peak in North America. Rainier is known, among other things, for its severe and ever changing weather patterns.

“We had a three day window where the weather was going to be really great,” VanDyke said.

The climbers began with a hike to the base of Emmon’s Glacier, which is between 7,500 and 8,000 feet above sea level.

The first night of the two-day climb they hiked past Camp Sherman, at 10,00 feet, and camped on the glacier above it at a place called Sherman Flats.

The next morning the group was up by 1:30 a.m. and began climbing by 2:30. The way up was icy and at an incline of 40 to 50 degrees.

“Basically, it would be like climbing up a double black diamond,” VanDyke said.

After 800 feet, Kultgen wasn’t feeling well and was forced to turn back. VanDyke and Stuart Smith climbed down with her, and when they returned the group continued towards the summit.

In all the ascent took six hours — the group navigating around crevasses and weaving their way up the mountain’s face.

“I’ve climbed a lot of mountains in the Rockies in Colorado, but I’ve never had to work that hard to get to the summit,” Wren said.

The fall and surprise help

After six hours, the climbers’ hard work paid off. Below them stretched the Cascade Range, bathed in low clouds and the morning sun, with Mt. Saint Helens in the distance.

The climbers soon began their long descent to Camp Sherman.

On the way down they encountered a large crevasse in the glacier known as a bergschrund. These canyons of ice are created when a large part of a glacier breaks off from the main body, and can be as deep as the glacier is tall.

It was above the edge of the bergschrund that disaster struck.

“To this day I still don’t know who slipped,” VanDyke said.

The group began to fall down the mountain towards the edge of the bergschrund, the edge of which turned up like the end of a ramp.

“We were literally launched off the ramp, I’ve been told we caught 10 ft of air,” Wren said.

“I remember being airborne and thinking, ‘it’s over, this is the end, we are totally going to die,’ and I remember being at peace.”

When the group hit the other side of the crevasse, Smith and VanDyke managed to slow the group down using their ice axes.

“I came to after the fall and I had a mouthfull of blood,” VanDyke said.

Wren was already conscious and making sure that Stuart Smith was responsive. According to Wren, the rope that was holding them all together was caught in the spikes Smith was wearing on his shoes for traction.

“Every time he would move it would cut the rope a little more,” Wren said.

Wren untangled the barely conscious smith and looked around for his niece Noelle.

She was nowhere to be seen.

Wren, who was relatively unharmed, began shouting for her and climbing in the direction of her rope. She eventually came to the edge of a small crevasse.

“I came over this lip and looked down and she was dangling in this crevasse upside-down,” Wren said.

Noelle Smith was anchoring the whole team to the mountain. She had fallen in a hole slightly larger than herself and kept the whole team from falling off the mountain.

“It’s a miracle that she fell into [the crevasse],” Wren said.

Another climber noticed the groups distress and came down the summit to assist them.

The climber, named Peter, was an experienced climber from Montana and trained in wilderness medicine and helped stabilize the group.

“That’s the point I knew that I was going to make it,” Wren said.

VanDyke, dangling at the end of the rope had been trying to call for help on a cell phone.

Calling up to Wren, he climbed 40 feet up the mountain with a dislocated leg and an ice axe. He called 9-1-1 that put him through to the ranger station.

“We’re dispatching rangers now, they’ll be there in an hour and a half,” they told him.

The rescue and trip home

The Mount Rainier National Park climbing rangers arrived quickly making the three day climb in under two hours.

They loaded Noelle smith into a helicopter, and began loading Stuart Smith in after her. Ross VanDyke was bundled up on a litter when there was a flurry of motion and the radios went silent.

“They came to get me and all of a sudden something happened,” VanDyke said.

According to VanDyke the rangers refused to tell him, but now it’s known that climbing ranger Nick Hall fell nearly 3,000 feet down the side of the mountain.

Rangers recovered his body when the weather broke.

Before they could load Wren into the helicopter a downdraft started to push it towards the side of the mountain. Wren heard the rotor blades getting closer, and two rangers threw themselves on her.

“I didn’t think about it until later, but that was another near death experience,” Wren said.

The other three hikers were airlifted out of the park, but Wren was forced to stay the night on the mountain with two rangers and hike down the next day.

Wren was sapped by fatigue, hypothermia and lack of food. She remembers asking to be left on the mountain.

“Continuing to live is the hardest thing you could possibly imagine,” Wren said.

It was due to the heroism of the rangers and the determination they inspired that Wren was able to make it to base camp. She and her fellow climbers are still grateful.

“The rangers were absolute heroes,” she said.