By Josh Siatkowski | Staff Writer, Jacob Stowers | Broadcast Reporter

After over a year of construction and many more years of planning, Founders Mall has reopened with a new centerpiece: the Memorial to Enslaved Persons, which will be dedicated Friday at 8:30 a.m.

The memorial, which was recommended by the Commission on Historical Campus Representations in 2020, addresses Baylor’s historical relationship with slavery. It recognizes the university’s construction through enslaved labor and Judge R.E.B. Baylor’s own possession of enslaved people, while continuing to acknowledge all parts of Baylor’s story.

“This is an invitation into a fuller history,” said Rev. Dr. Malcolm Foley, a member of the commission and special adviser to President Linda Livingstone.

Along with evolving and enriching the telling of Baylor’s history, the designers explained the memorial is rich with symbolism and even a dynamic, living place.

Additive, Not Subtractive

The commission’s 94-page report, which researched the recommendation and decision to create the memorial, faced the challenge of not just telling another part of Baylor’s history but fitting it into the larger, more complex story. In Central Texas, slavery was almost everywhere in 1845, when Baylor was built in Independence. According to Director for Advancement Marketing Dr. Todd Copeland, 50% of Washington County’s population — where Independence is — was enslaved in 1860.

While this statistic alludes to Baylor’s use of enslaved labor for the construction of the original campus, there’s also the more personal story of Judge R.E.B. Baylor, for whom the university is named and a statue stands on Founders Mall.

“In 1860, Judge Baylor was reported as owning 33 enslaved people,” Copeland said. “And on these census schedules, those people are not named. They’re only identified by age and sex, so there’s a gap in the historical record.”

What the memorial attempts to do is fill those historical gaps — the very literal gaps of unnamed people, and the more figurative gaps of the lack of slavery’s recognition on campus.

But for the commission, it didn’t mean forgetting other parts of Baylor’s history. While the statue of Rufus Burleson — also a slave owner — was moved in 2022 to a place of less prominence by Burleson Hall, nothing on Founders Mall was removed. When discussing that question for Judge Baylor’s statue, the answer was easy.

“We decided as a commission ‘no,’” Foley said. “We’re an educational institution, and so that means the goal is to educate. So if there’s a space that doesn’t have the proper context, then we add that context.”

A Tapestry of Symbols

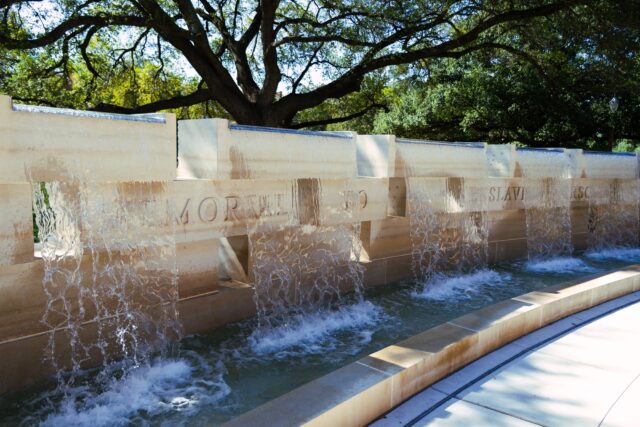

One thing pedestrians may not immediately notice in a tour of the memorial is that its meaning goes much deeper than the surface. From the limestone’s connection to Independence to the religious symbolism of seven water fountains to the 33 gaps in the focal wall, almost everything on the site is imbued with significance.

One of the most visible forms of symbolism, though, is the pair of scriptures on the wall.

“[The fountain] is flanked by two scriptures, one being the way that the Lord introduces himself to his people, especially throughout the Old Testament: ‘I am the Lord, your God, who freed you from the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.’” Foley said. “And then on [the other] side Christ’s words in John 8, where he says, ‘If the Son makes you free, you will be free.’”

The verses “get us thinking, both materially and spiritually,” Foley said.

“We want to be reminded specifically of the history of actual racialized chattel slavery, where exploited labor essentially built this campus,” Foley said. “That material history is something that we want to be constantly reminded of, but we want to pair it … with spiritual liberation — that Christ has actually set us free.”

Between the verses, the wall is layered with meaning. With seven rushing fountains of water, those passing through are met with purifying, liberating and Christian imagery.

“It is significant, not only that we have water, but seven water fountains, because seven is the number of completion, theologically,” Foley said. “But also, water has such deep Christian symbolism, particularly to think of the waters of baptism, to think about even the waters of the Red Sea, as the people at the people crossed over it in liberation.”

The limestone itself also contains meaning. Sourced in Central Texas, it’s a tribute to Baylor’s original limestone buildings in Independence. The stone pattern on the back also mirrors hand-cut rock, honoring the labor of the enslaved builders. Further, the 33 gaps in the wall are there to symbolically account for the 33 enslaved people held by Judge Baylor, who are not named in the records.

A Dynamic, Living Space

Beyond being just a physical spot on campus, the memorial’s designers see it as an animated being capable of changing attitudes and campus culture. Ian Scherling, a landscape architect for Boston-based firm Sasaki who managed the project, said that dynamism was part of the goal in designing the space at Baylor.

“I actually think this place is an animate object,” Scherling said. “It’s meant to change moods. The way that the light hits the wall at different times of day changes the feeling within the space.”

Foley said the same, highlighting the multi-sensory effect of walking through the memorial.

“You hear it before you see it,” Foley said. “This space becomes a full sensory experience.”

Part of the vision for the memorial is to embed it in the university’s cultural identity, striking a balance between inspiring change and seamless integration.

“Our approach to that was to respect Founders’ Mall and also to make this memorial feel like it’s meant to be there,” Scherling said.

But at the same time, it commands attention, Foley said.

“It reshapes all of the walking paths as well,” Foley said. “So it basically forces a kind of engagement.”

Through the guiding paths and other forms of engagement, Foley said the memorial can become a conduit for changing Baylor’s culture and identity.

“As I look at discussing the coming years, I’m thinking about ways we can work this into campus tours,” Foley said. “I’m thinking about leading a chapel in this space, but on this material. There are ways to work this into the life of the institution, to work this history into not only something that everyone knows, but something that everyone recognizes that they’re a part of.”