By Lalita Clozel

Tribune Washington Bureau via McClatchy Tribune

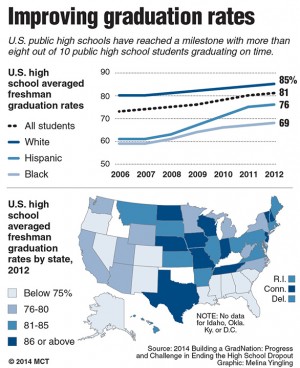

WASHINGTON — The national high school graduation rate has reached a record high of more than 80 percent, but disparities based on students’ racial, socio-economic and disability status remain alarming, according to an annual report by America’s Promise Alliance, a nonprofit group founded by former Secretary of State Colin Powell.

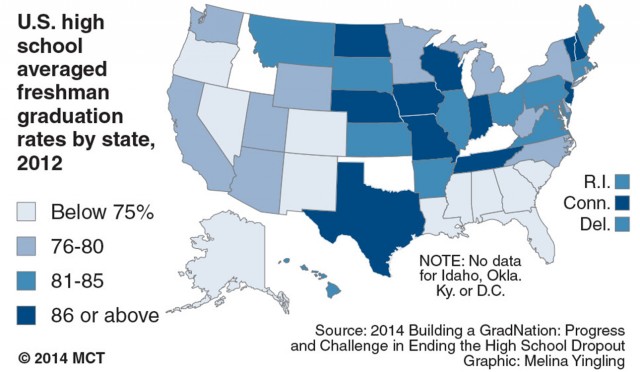

An estimated four out of five public high school students obtained their diploma in 2012, according to the report, which used the latest available data from the Department of Education. But figures were lower for minority students. Seventy-six percent of Latino students and 68 percent of African-American students graduated, the report found.

“We have to be honest that this is a matter of equity and that we have to change the opportunity equation,” Education Secretary Arne Duncan said Monday. “All of America’s children are our children.”

Recent improvements in the nation’s high school graduation rate _ which has risen 8 percentage points in six years _ have been driven by the closure of so-called “dropout factories,” typically high-minority schools that graduate less than 60 percent of students. In 2002, those schools enrolled almost half of all African-American students but by 2012, that number dropped to only 23 percent.

The results underscore the need for more federal funding to ensure that all students are provided with the same opportunities, said Daniel J. Losen, the director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA.

“We still have many school districts where it looks like apartheid in America,” he said. “It’s going to require more than the contributions of the private sector and the competitive grants of the federal government.”

Several categories of students face persistently lower odds of graduating, including those with physical and mental disabilities, those from low-income families and those learning English as a second language.

The nation’s graduation rate began decreasing in the 1990s, but with rising awareness of the dropout crisis in certain school districts, states and districts began implementing reforms in the 2000s, which are now beginning to bear fruit.

“Schools were for a long time ignoring this facet,” said Losen. “They were focused for the longest time on test scores.”

Joanna Hornig Fox, the deputy director of the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University and one of the report’s authors, attributed the improved rates in part to recent federal education reform bills, including No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top, which implemented nationwide standards and performance-based funding for public schools.

Fox said that thanks to efforts to ensure “students do a great more deal of writing and explain their thinking,” now students in poorer districts are “not just filling in the blank.”