By Mackenzie Grizzard | Assistant News Editor

For 125 years, The Baylor Lariat has been the constant, steady voice for Baylor students, by Baylor students. As administrations changed and the world carried on, Baylor’s student journalists published the news, wrote opinion columns, covered athletic events and analyzed the arts.

But in the spring of 1980, the lights went out in the newsroom. Students still went to class, and Fountain Mall still hummed with springtime chatter — but the newsstands remained empty.

The Baylor Lariat, the voice for the student body for the past 80 years, was silent. An empty newsroom was echoed only by the fateful last stand of the Feb. 22, 1980, editorial.

“When we opened this editorial page 30 Lariats ago, we promised an honest, hard-hitting page of opinion — our opinion,” the editorial reads. “Now that’s been denied us.”

A month earlier, Playboy Magazine had its sights set on Baylor. Photographer David Chan had done features like “Girls of the Ivy League” and “Girls of the Pac 10” with plans to continue into the Southwest Conference, which included Baylor at the time.

When news of female students potentially being photographed nude reached a conservative, Christian institution like Baylor, it was met with apprehension by the administration.

“They ran a thing called ‘Playgirls of the Southwest Conference,'” said Dr. Doug Ferdon, former chair of the journalism department. “At the time, it was a big deal to have women bare their breasts, but the Baylor girls did not; they just unbuttoned another button.”

On Feb. 1, 1980, Baylor President Abner McCall said any female student who posed nude for Playboy would face disciplinary consequences. Dean of Student Affairs W.C. Perry said the administration would not necessarily object to a clothed pose, such as a swimsuit, but nudity was a serious concern.

After McCall’s official statement, a Playboy spokesperson told The Lariat that the company would assist students with legal aid if they faced disciplinary action.

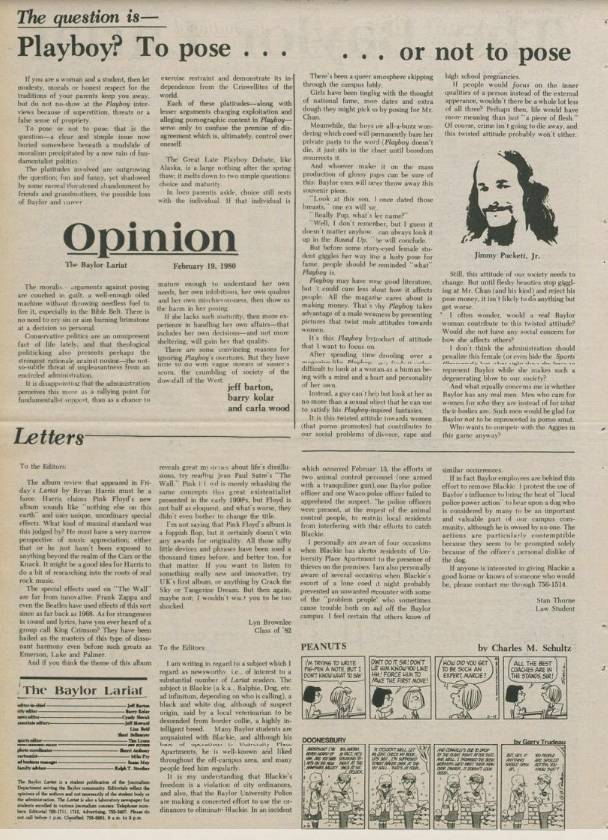

On Feb. 19, The Lariat officially put its hat in the ring, publishing an editorial that took a harsh stance against President McCall’s decision.

“The moralist arguments against posing are couched in guilt, a well-enough oiled machine without throwing needless fuel to fire it, especially in the Bible Belt,” the editorial reads. “There is no need to cry sin or aim burning brimstone at a decision so personal. Conservative politics are an omnipresent fact of life lately, and that theological politicking also presents perhaps the strongest rationale against posing — the not-so-subtle threat of unpleasantness from an encircled administration.”

The editorial, signed by then-Editor-in-Chief Jeff Barton, City Editor Barry Kolar and Assistant City Editor Carla Wood, slammed the administration for encroaching on the female student’s right to “handle her own affairs,” calling it a “rallying point for fundamentalist support.”

“Around 1975 to 1985, the fundamentalists in Texas kept trying to take over Baylor,” Ferdon said. “We were kind of the younger people they brought in to help buttress the faculty against fundamentalism.”

On Feb. 21, McCall clapped back, accusing The Lariat of publishing an editorial that not only was against Baylor’s Christian mission but also encouraged students to violate university policy. McCall and the administration declared that The Lariat would not be able to publish editorials or news stories that promote “ideas not keeping with traditional Baptist doctrines.”

“If editors can do their job and report the news and get the facts straight, they won’t have a problem,” Ferdon said. “But once they start writing columns or editorials that are against something Baylor promotes, they’ll run into trouble.”

McCall told Barton and other Lariat editors that future editorials should focus on less serious topics and that The Lariat could continue covering news as long as it was the “right kind” of news.

“Herbert Reynolds and Abner McCall, who were in charge of Baylor at the time, didn’t have a lot of choice because they were caught between the fundamentalists on one hand and student free speech on the other,” Ferdon said.

The battle reached its climax in the Friday paper published that week, with another editorial announcing the walkouts by the editors and several staff members.

“We respect Dr. McCall a great deal — and we have made every effort to understand each plank of his position,” the editorial reads. “He has accused us of attacking him personally and of blaspheming the precepts of this university. Respectfully, we must argue that we have done neither. We often disagree with the president, and when we do, it is because we have an honest difference of opinion with his policies — not because we have any dislike for Dr. McCall as a man.”

A few days later, McCall fired back with his own statement, emphasizing that Baylor was well within its rights to decide what is and what is not published.

“If any student editor or reporter sincerely feels that he or she cannot work within the policies herein set forth, he should resign from The Lariat staff,” McCall said in the statement.

After a 50–100 person student protest outside Pat Neff on Feb. 27, an emboldened Barton continued to lobby student congress to make the administration reconsider its decision.

“As a private university, you have to either hope that there’s some sort of local law or regulation in place that protects your editorial independence,” said Sommer Dean, Fred Hartman Distinguished Professor of Journalism and licensed attorney.

The next day, student congress voted 20–1 to support McCall, with some accusing The Lariat of only publishing favorable letters that agreed with the editor’s stance.

Despite this loss, Barton, Kolar and News Editor Cyndy Slovak published one last editorial on Feb. 29 to defend their position.

“Even though the administration will be carrying on its policies to a new set of transients after we are gone, we hope students will no longer accept the tired rationale that what is said and done now will not matter,” the editorial reads. “We hope the administration cares enough to listen. We hope students care enough to question. But that time may not have arrived. And that’s too bad.”

Shortly before publication, without the editors’ consent, Lariat Adviser Ralph Strother removed a section of the editorial to avoid further controversy. When the editors objected, he recommended firing Barton, Slovak and Kolar.

“It wasn’t really the news in The Lariat that caused all the trouble,” Ferdon said. “[Strother] went down to the tribunal that night and took one paragraph out, and that caused most of the trouble.”

On March 3, the Baylor Board of Publications voted unanimously to fire all three editors. Over a hundred students gathered in protest, according to the Baylor Line.

Several other professors in the journalism department either resigned or were fired after expressing support for The Lariat, scholarships were canceled and Baylor was removed from several national journalism societies.

Publication of The Lariat was suspended for three weeks. Students lost scholarships and professors lost tenure. McCall would later equate the controversy to “a wart on his toe.”

“For me personally, I’d probably be on the side of the journalists,” Ferdon said. “I would be against them censoring that, but I was also aware that when I came in, I had to make a lot of people happy.”

Several months later, the Playboy feature was published — and roughly 80 Baylor women had been photographed. According to Ferdon, he was not aware of any Baylor student posing completely nude for the final photos.

The Lariat resumed publication after the dust had settled, and the three fired editors did not return. The “wart” on McCall’s foot was successfully lanced, but the deep scar of a censorship controversy remained a part of Baylor’s campus — and Lariat history.