By Jenna Fitzgerald | Copy Editor

While spirited Americans are used to sporting green and celebrating all things Irish on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17’s designation as a public holiday is an indicator of something much deeper for the Emerald Isle: its profound spiritual landscape and religious history.

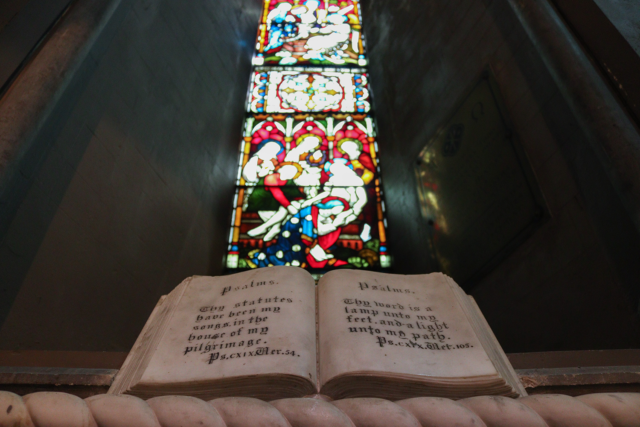

Following a long-standing tradition of Celtic paganism, Catholicism arrived in Ireland around the fifth century. Bolstered by missionary figures like Palladius and St. Patrick, the faith took root, spreading throughout Ireland and earning it the title of ‘the most Catholic country in the world.’

Sister Mary Glynn grew up in the West of Ireland before joining the Congregation of the Sisters of Mercy in 1971. According to the Central Statistics Office, the population of Ireland was 93.9% Catholic in that year. Glynn said growing up, she didn’t know anyone who wasn’t Catholic, and everyone would attend Mass because “you just went, and that was it.”

“I suppose [the Catholic Church] was no more domineering in Ireland than it was in any other place in the world, but the Irish people wouldn’t have questioned it,” Glynn said. “My parents wouldn’t have questioned what the priest said or what the nun said.”

Dr. David Mitchell, an assistant professor of religion at Trinity College Dublin, said the gradual establishment of British rule and the Protestant Reformation resulted in religious discord, as solidly Catholic Ireland faced newly Protestant Britain.

“British involvement in Ireland began in 1169 when the Normans invaded, and really from then on, there was some kind of English or British involvement in Ireland,” Mitchell said. “I suppose it got serious after the Reformation, because then you had the British monarchy becoming Protestant and wanting to impose that on all of Ireland. Then you had the plantations of the early 1600s, when lots of British settlers were sent over to live in Ireland in order to secure Ireland for the crown.”

While differences of principle between the Catholic Church and the Protestant Church of Ireland may seem small to outsiders, Mitchell said the feelings are intensified for the Irish people themselves.

“People who are similar can be very divided,” Mitchell said. “[Sigmund] Freud had this idea of the narcissism of minor differences; in other words, sometimes the people who are the most alike hate each other the most, and you can see this in lots of different ethnic conflicts around the world. This is what has happened in Ireland. People from outside Ireland can’t understand why all these Christians are fighting each other, but when you’re in Ireland, the differences between Protestantism and Catholicism are magnified to such an extent that it’s a grounds for hostility.”

Mitchell said over time, religious and political divisions aligned, with Protestants supporting British unionism and Catholics embracing Irish nationalism.

“By the time you get to the 20th century, you’ve got two kinds of nationalist movements in Ireland — a British one in the North and an Irish one in the South — that are kind of facing off against each other,” Mitchell said. “It looks like there’s going to be a civil war, but then Britain decides to partition Ireland and create Northern Ireland and put a border there to try to keep the peace.”

Mitchell said in more recent times — particularly regarding the civil rights movement and the 30-year Troubles in Northern Ireland, which saw violent conflict between Protestant loyalists and Catholic republicans — the religious aspect has lessened in prominence while the political aspect has become dominant.

“By the time you get to the late 20th century, it’s not really a religious conflict at all,” Mitchell said. “It’s a conflict over national identity and borders and equal treatment. But nevertheless, you can’t escape the religious heritage of Britishness and Irishness, which kind of grew out of Protestant and Catholic identities.”

As Ireland has secularized, it has seen a decrease in churchgoing and an increase in socially liberal laws, including referendums on abortion and divorce. Glynn said today, greater acceptance of all religions can be attributed to flourishing diversity and education.

“There’s a certain kind of attitude that has arisen now: live and let live,” Glynn said. “The tolerance would come a lot from education — young people being educated together with different races and different religions all in one classroom. You’d say America is a melting pot, and it is. But Ireland, in a smaller way, is also a melting pot now.”