By Thomas Moran | Staff Writer

According to recent Baylor research, an individual’s perceptions of God might influence one’s political views. Baylor sociology professor Dr. Paul Froese and Rice University postdoctoral fellow Dr. Robert Thomson used the Baylor Religion Survey for their research and the writing of their two published academic papers.

The two worked on the papers together while Thomson completed his doctorate in sociology, which he earned last year. Froese and Thomson set out to find how individuals navigate situations in which political and religious beliefs come into conflict and how they determine which perspective to prioritize.

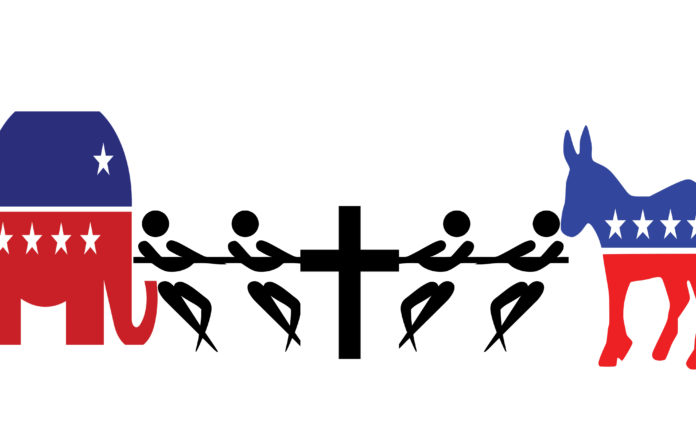

“On issues of economic justice, the democratic party and the republican party definitely have different approaches to addressing justice, equality, economic equality, that sort of thing,” Thomson said. “Religious organizations also have a variety of approaches.”

The first paper, published last year in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, is titled “God Versus Party: Competing Effects on Attitudes Concerning Criminal Punishment, National Security, and Military Service.” The paper discusses the relationship between one’s understanding of God and one’s political beliefs regarding punitive policy and related matters.

Capital punishment, strong military and strict punishment for crime are normally associated with a more conservative and, consequently, republican political perspective, according to the GOP.

However, data from the survey shows that democrats who perceive God to be more judgmental, dissociated or stern tend to have far more conservative views on these political issues than other democrats.

“Partisanship … doesn’t necessarily always predict your policy preferences because you might not know what your party thinks about a certain issue,” Froese said. “But what we’re finding is image of God is as predictive of policy preferences as your party affiliation. So if somebody has an image of God as being quite judgmental and wrathful, they might have this kind of eye-for-an-eye tooth-for-a-tooth morality.”

The second paper, published in the Sociological Forum this past January, is titled “God, Party, and the Poor: How Politics and Religion Interact to Affect Economic Justice Attitudes.” The paper examines the relationship between one’s understanding of God’s nature and one’s beliefs regarding economic equality and related issues.

Democratic policy regarding economic justice is often more liberal and are geared toward income equality through social welfare taxation and similar programs.

According to data from the Baylor Religion Survey, republicans who view God as a kind and intimately involved entity often have a far more liberal perspective regarding economic justice issues.

“What we’re arguing is that conservatives that have this very loving benevolent God image, will tend to have a morality which is about caring for others, so they then in turn are more likely to support social welfare programs,” Froese said.

Fort Worth senior Sierra Sears was not surprised that perceptions of God can lead people away from their partisan ideals.

“I think religion is kind of a system in itself,” Sears said. “So, if your religion talks about how God is kind and forgiving and accepting, I’m sure you would want to be the person that stands up for things like gun control and say ‘this is wrong,’ … I think it [religion] has the ability to sway people’s beliefs even if they are democratic or republican.”

Froese and Thomson agree there are common misconceptions regarding religion and political belief. For example, religiosity is often equated with conservatism. Likewise, a liberal point of view is often viewed as completely non-religious.

“I think it is sort of a misconception that the political right and left represent religion versus non-religion,” Thomson said. “In fact, there is religion on both sides, on the left and the right. What we were interested in is how do these two sources of moral authority speak to each other and when one comes into conflict with the other, which one wins?”

In his view, whether religiously influenced beliefs or party affiliations “win” depends on the issue at hand.

The research is significant from a statistical perspective because one would expect a person’s image of God to be predictive of policy attitudes, Froese said. Party affiliation and loyalty toward that party would be more logical predictors of policy attitudes.

“You’d think that [party affiliation] essentially would explain almost all of that person’s political views,” Froese said. “But what we’re finding is that it doesn’t. You can show that religious beliefs like your understanding of God, can influence your policy preferences.”