By Kristina Valdez | Arts & Life Editor

To get to the Family Abuse Center, you must follow vague directions that are not available online. After signing a confidentiality agreement, you can then volunteer or speak with a Family Abuse Center representative.

To enter the Family Abuse Center in Waco, you must stand on the opposite side of double doors and speak through the intercom about your business there that day.

Unmarked and protected, the Family Abuse Center has sheltered and supported victims of domestic violence since 1980. A team works tirelessly to help and educate communities and families about the plague of domestic violence.

“It’s not just physical,” said Katie Matula, development coordinator of Family Abuse Center. “It’s kind of like cancer — it can affect anyone … A victim can experience multiple types of trauma, whether it is emotional or financial or physical.”

According to the Texas Council for Family Violence, one in three Texans will experience domestic violence at some point in their lifetime.

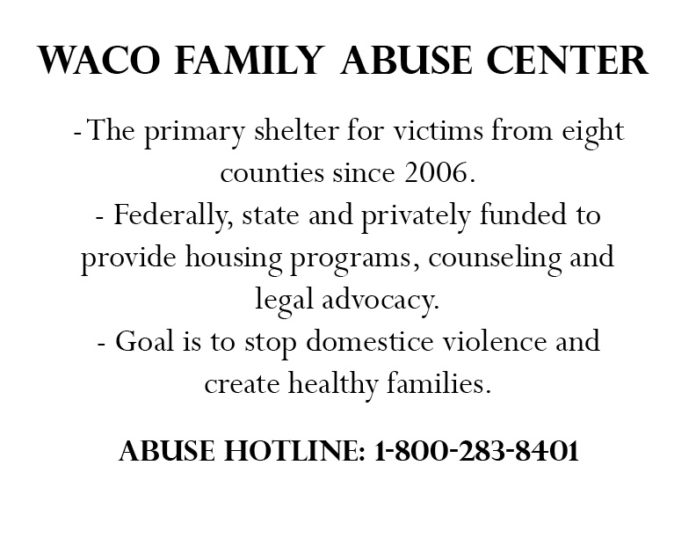

The current location in Waco has been the primary shelter for victims from eight surrounding counties since 2006. Family Abuse Center is federally, state and privately funded to provide housing programs, counseling and legal advocacy. Permanent supportive housing, transitional housing, rapid rehousing and two private housing are offered to family units who need a way out without turning to the streets.

“The leading cause for homelessness among women and children is domestic violence,” Matula said.

In 2016, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Bureau reported that 80 percent of homeless women and children were victims of domestic violence.

“Research has shown that housing programs are highly effective with domestic violence victims in getting them the support they need to stay away from their abuser,” Matula said. “It’s not just a matter of [victims] choosing to go back, but a matter of not being able to pay or rent or pay for their kids’ medication.”

Matula has worked for the Family Abuse Center since 2014 after receiving her master’s in social work from Baylor in 2013.

“I would love to work myself out of a job,” Matula said. “Family Abuse Center’s goal is to, yes, end domestic violence, but also create healthy, loving families.”

Family Abuse Center offers programs like BOOST, a teen dating violence prevention program, and H.O.P.E.S., a parent support program that helps provide better care for small children. These programs are offered to McLennan County through schools and Family Abuse Center. They are preventative steps in educating children about healthy relationships.

“I’m hopeful,” Matula said. “Every report I get brings me down a little bit, but I know we are moving in the right direction.”

Matula said a common misconception about domestic violence is believing that once a victim has left, everything should be okay.

“Another thing that people don’t think about as far as domestic violence is concerned is that sometimes abusers will put the victim’s name on the lease and not pay rent,” Matula said. “When it all comes down to it, the victim is left with multiple evictions under their name even though they had nothing to do with it.”

Housing coordinator Melissa Ishio will have worked with the Family Abuse Center for two years in March. Ishio tries to help the most people with what little bit of funding she has.

“The hardest part of my job is not having enough money,” Ishio said. “I have to say no to people. There is always someone else who needs it. [I want] to give without deciding who or who is not worthy.”

Ishio said domestic violence impacts the community in more ways than people realize. For example, of the recent mass shootings, a relationship between domestic violence and mass murders are common. Shooters from the mass shootings in Sutherland Springs, Las Vegas, Orlando, Fla. and San Bernardino, Calif. had a history of violence against women.

According to a study done by Everytown for Gun Safety, in 54 percent of mass shootings, the shooter killed a partner or family member.

“It’s a much more prevelant issue than people even begin to know about or think about,” Ishio said. “It is behind so much of the violence we see in our country.

For her clients, Ishio has learned what it means to live with trauma.

“It affects everything that you do and your whole perception on things,” Ishio said. “It’s huge how pervasive and debilitating it can be for someone. It’s kind of like living in a war zone — our clients have PTSD, too, from that hyper vigilant, ever-aroused state that they lived in for so long.”

To Ishio and Matula, the definition of a success story is different for every client, but success includes opening up the paper one day and not finding their client’s name listed as deceased.

“[Domestic violence] does not discriminate on the basis of race, sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity, age and you can go on and on,” Ishio said.