A book written by an alcoholic about being an alcoholic is not for everyone. A book written about being a woman in the midst of double standards, all-night binge drinking, and endless self-discovery can be for everyone.

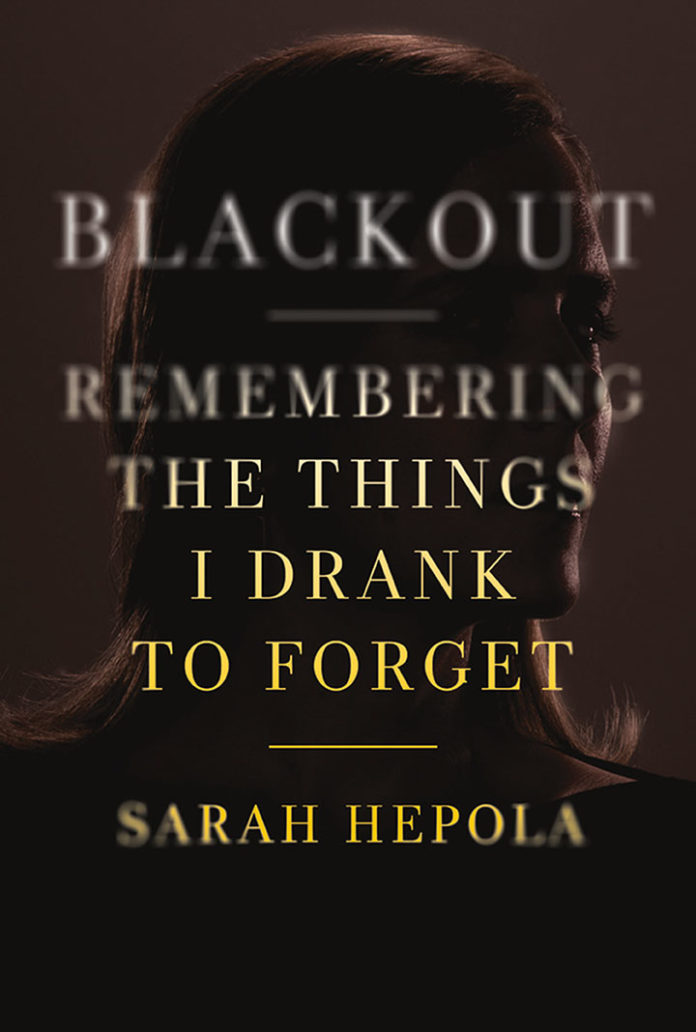

Sarah Hepola’s brutally honest autobiography and New York Times bestseller, “Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget,” is not for the complacent, wavering reader. This novel draws out the darkest inner workings into a humorous light with tastefully placed swear words and outlandish stories about the drunk and disorderly.

“Alcoholism is a self-diagnosis,” Hepola wrote. “Science offers no biopsy, no home kit to purchase at CVS. Doctors and friends can offer opinions, and you can take a hundred online quizzes, but alcoholism is something you must know in your gut.”

There were the stolen sips of Pearl Light at age 7, the one beer that led to one too many at age 11, the dependency on alcohol at age 20 and the ultimate breakup with alcohol at age 35. But, as the title suggests, the book is about more than alcohol and the inability to know when to stop. The book confronts Hepola’s suppressed memories head-on and makes readers think about what situations are similar to their own lives.

“Be kind to drunk people, for every one of them is fighting an enormous battle,” wrote Hepola.

Dedicated “to anyone who needs it”, the book offers the worst of herself and the best of her memories. To understand the severity of Hepola’s alcoholism, the term “blackout” must be clear.

“The blood reaches a certain alcohol saturation point and shuts down the hippocampus,” Hepola wrote.

Hepola said that it can be extremely difficult to tell if someone is experiencing a blackout.

“But in a blackout, a person is anything but silent and immobile,” Hepola wrote. “You can talk and laugh and charm people at the bar with funny stories of your past.”

Throughout the book, Hepola was either getting drunk, drunk or waking up from a blackout. There is an urge to laugh at Hepola’s random flashings at unassuming elderly men or her mooning people in bumper-to-bumper five o’clock traffic. But then you ask yourself, is this her rock bottom? No, not yet.

In the middle of all of this, there were Hepola’s friends. They filled in the gaps where her memories lacked, told her the truth and tucked her into bed several times. It was refreshing to know that just as alcohol defined Hepola’s life, her friends did, too.

“Some recovering alcoholics believe you need to distance yourself from your old friends,” Hepola wrote. “They are triggers and bad influences. But what if your friends were the ones who saved you? Who closed out your bar tab and texted with you until you made it home safely?”

Although it is printed that the book is written “to anyone who needs it,” the vulnerability and strength of Hepola’s life denotes and caters to an audience of women. The book is beautifully written to the girl, the teenager and the woman with subtle compassion.

The parts of the book that talk about getting your period for the first time, extreme dieting and about having sex are unspoken truths. Hepola refuses to shy away from the pain of the woman she was and is.

“We all want to believe that our pain is singular,” Hepola wrote. “that no one else has felt this way – but our pain is ordinary, which is both a blessing and a curse. It means we’re not unique. But it also means we’re not alone.”

Alcohol drowned the truth and the pain. In the bubbles and swirls of alcohol, Hepola thought she found her voice, her courage and her sexiness. For other women, the same could be found in a relationship or in materials. But there is a moment of breaking – Hepola had it. She saw what was left of herself and made the decision to be sober.

“I don’t know how to describe the blueness that overtook me,” Hepola wrote. “It was not a wish for suicide. It was an airless sensation that I was already dead. The lifeblood had drained out of me.”

Hepola told Salon, an online arts and culture magazine, that she was afraid that when the book came out, nobody would care. But while we live a world full of body issues, alcoholism and depression, someone will always care about a book that will make you nod your head, pump your fist in the air and smile because that is one more person in this world who gets it.