By Gavin Pugh | Digital Managing Editor

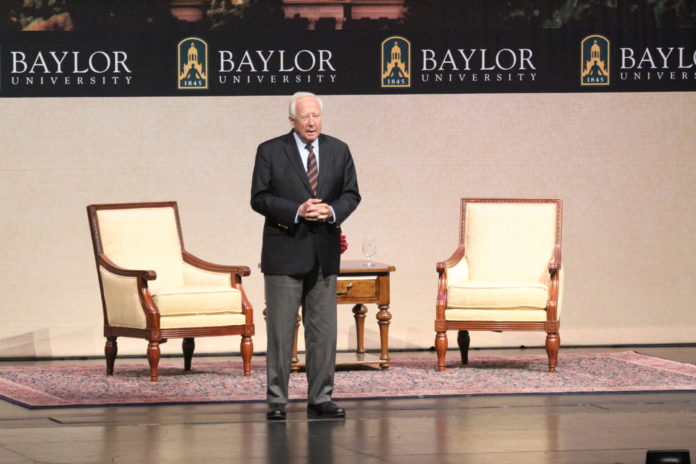

David McCullough found himself shopping for pecans during one of Boston’s worst blizzard seasons in 2014. The shop attendant assisting him recognized his voice from his commentary on television and told McCullough how his tone cured him of insomnia. McCullough, speaking to a crowd at Waco Hall for this year’s Beall-Russell Lecture in the Humanities Monday afternoon, said this interaction with the attendant was the best compliment ever paid to him.

McCullough is a two-time Pulitzer and two-time National Book Award recipient. He also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which is the highest award a citizen can be given. He has written scores of books, most notably his biographies on the Wright brothers and presidents Harry Truman and John Adams, the latter of which was turned into an HBO series in 2008.

McCullough cited curiosity as the key mechanism that drove these people to leave lasting legacies.

“Curiosity is, in many ways, what separates us from the cabbages,” McCullough said. “It’s that drive that comes with knowing something, and you want to know more. It’s accelerative, like gravity.”

Particularly with regard to the Wright brothers, McCullough noted their curiosity and avid love for books despite their lack of a college education.

“The reading they did was the content of a liberal arts education,” McCullough said, adding that, though they were not trained in physics or mathematics, they still managed to get a plane in the air.

To an enthused crowd of predominantly liberal arts scholars and students, as the Beall-Russell lecture series is hosted by Baylor’s College of Arts and Sciences, McCullough’s acknowledgement of the importance of such an education was met with applause. McCullough went on to make the distinction between consuming information and being educated.

“Information isn’t learning. Information is useful; it can be important nationally on more than one occasion. It can save time, but it isn’t learning,” McCullough said. “For example, if you memorized the World Almanac, you wouldn’t be educated – you would be weird.”

Part-time history lecturer Lisa Lacy said that though some people don’t have access to a liberal arts education, there is a fundamental difference between information-seeking and education.

“People have confused education with training,” Lacy said, citing technical programs such as those offered at Texas State Technical School.

However, this distinction wasn’t an idea exclusive to just the professors and lecturers in the room.

Students also nodded their heads in agreement when McCullough said, “Alas, we’ve been raising two generations of young people who are historically illiterate.”

Dallas freshman Katie McMillin, who is working toward a liberal arts degree to round out her pre-med track agreed with McCullough.

“We push a lot of learning towards knowing facts and math and formulas for how to solve problems instead of studying history,” McMillin said.

It is in this study of history and the liberal arts – in that gravity-like curiosity McCullough spoke of – that value is found in other people’s struggles and triumphs.

“Perspective is also something that knowing history gives you,” said David Smith, senior lecturer in American history.

That perspective gained through the study of history isn’t limited to typical hot-button issues, according to McCullough.

“History isn’t just about politics and war,” McCullough said. “Politics and war are of utmost importance to be sure, but they’re not everything.”

Rather, that perspective has intrinsic value to the individual. For example, the Wright brothers learned from coastal birds that liftoff is achieved by flying into headwind, McCullough said. He used this newfound perspective to draw parallels between achieving flight and persevering through difficulties.

“We’re interested in the easy way out,” Smith said.

Smith said people equate effort and hardship with unnecessary pain and avoid effort altogether. Though McCullough’s curiosity led him to realize the headwind was where the nation’s most notable figures grew, it was through their self-expression – their letters, poetry and journals – that he learned the most about them.

“Don’t you think that’s the value of a liberal arts education? It teaches you to express yourself,” Lacy said.

Just as people like John Adams, Wilbur Wright and Thomas Jefferson endured hardship, their self-expression was not kept to themselves, nor was it self-taught.

“There never was a self-made man or woman; that’s a fantasy,” McCullough said.

McCullough, noting how his time at Yale was so formative, particularly due to his professors, encouraged the students in the audience to thank their professors and others who have influenced them.

The first cool days of fall are settling in on Baylor’s campus – the wind’s noticeable crispness means the leaves will change soon, though it’s not quite to the scale of a Boston blizzard McCullough endured while shopping for pecans. The Wright brothers had their share of windy days, but they flew into that wind — McCullough encouraged the crowd to do the same.

Lariat reporter Brooke Bentley contributed to this article.