By Sarah Jennings, Reporter

Warm aromas drift and swirl out of the little blue kitchen. A timer dings. The toothpick slides into the cornbread, then cleanly out. Lying on the cluttered counter is an open cookbook.

Much like the archetypal housewives who used them, the cookbook was a cornerstone to daily family and community life. But they are often forgotten or seen as too mundane for academic study. However, 25 years ago, Elizabeth Borst White—a retired librarian from Houston—began collecting these valuable depositories of history and culture. Utilizing eBay Inc., White began her collection simply for the pleasure of cooking. She quickly recognized the intellectual value they held.

“Especially the community cookbooks, they reflect the community,” White said. “On some of the Texas cookbooks there’s a lot of deer or doves. That’s what they had in the community to eat.”

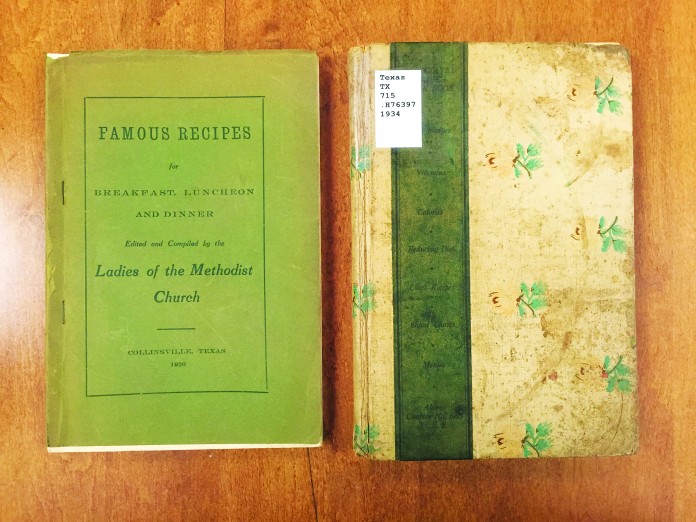

When White began her collection, she was in charge of historical medical collections at the Houston Academy of Science. Original research on cookbooks was rare, and she noticed a need for compiling collections of cookbooks for study. Those very cookbooks she is now donating to the Texas Collection at Baylor in order that researchers may gain from her work. She has donated more than 1,000 books. Her donations are in top-condition, protected with archival covers and her personal bookplate.

Amie Oliver, curator of print materials at the Texas Collection, said the collection includes a wide variety and number of texts and images. From rare books—like a Latin text from 1482—to 19th century Baylor photographs, Oliver said the library seeks to be inclusive of many time periods, disciplines, religions and ethnic groups.

Although Baylor is a Baptist university, materials on Catholic, Methodist and Jewish culture are collected to tell the complete history of Texas.

“Many people assume it’s just history, but we cover all disciplines. We collect anything that tells the complete story of Texas: history, music, art, religion, literature, the people, and the pioneers,” Oliver said. “Our cookbook collection is a good representation of that. There are about 5,000 Texas cookbooks, but the collection grows all the time.”

For many years, cookbooks were the only way women published. These texts gave a voice to their experience and stories. Women produced cookbooks as a way to raise money for churches, committees, and schools. According to recent study by Dr. Sarah Walden, women’s sales provided a platform, even if somewhat hidden, to speak and to support social causes.

“Some of the very first community cookbooks were during the Civil War,” White said. “Women produced these cookery books to get money to help soldiers or to help their families. Women individually had cookbooks before that, but it was the Civil War that really started it for community cookbooks.”

White said cookbooks have evolved over the years. Paragraph form was standard up to the early 20th century, and this allowed for commentary and regional character to seep through. Abbreviations became standardized in the 1920s and 1930s. The plastic comb binding emerged in the 1940s. Now the trend is to use Internet compilations to find recipes.

The table brings us together. Family dinners, friendly chats and deep conversations all begin around the breaking of bread. It’s no wonder cookbooks are testaments to the depth and variety of the human community. They’re so much more than a list of measurements; they’re also anecdotes and family photos. They’re collections of our common memories and nostalgic flavors.

“If we don’t get along about anything else, we all agree we need to eat,” Oliver said.