Shannon Barbour | Staff Writer

By Shannon Barbour

Staff Writer

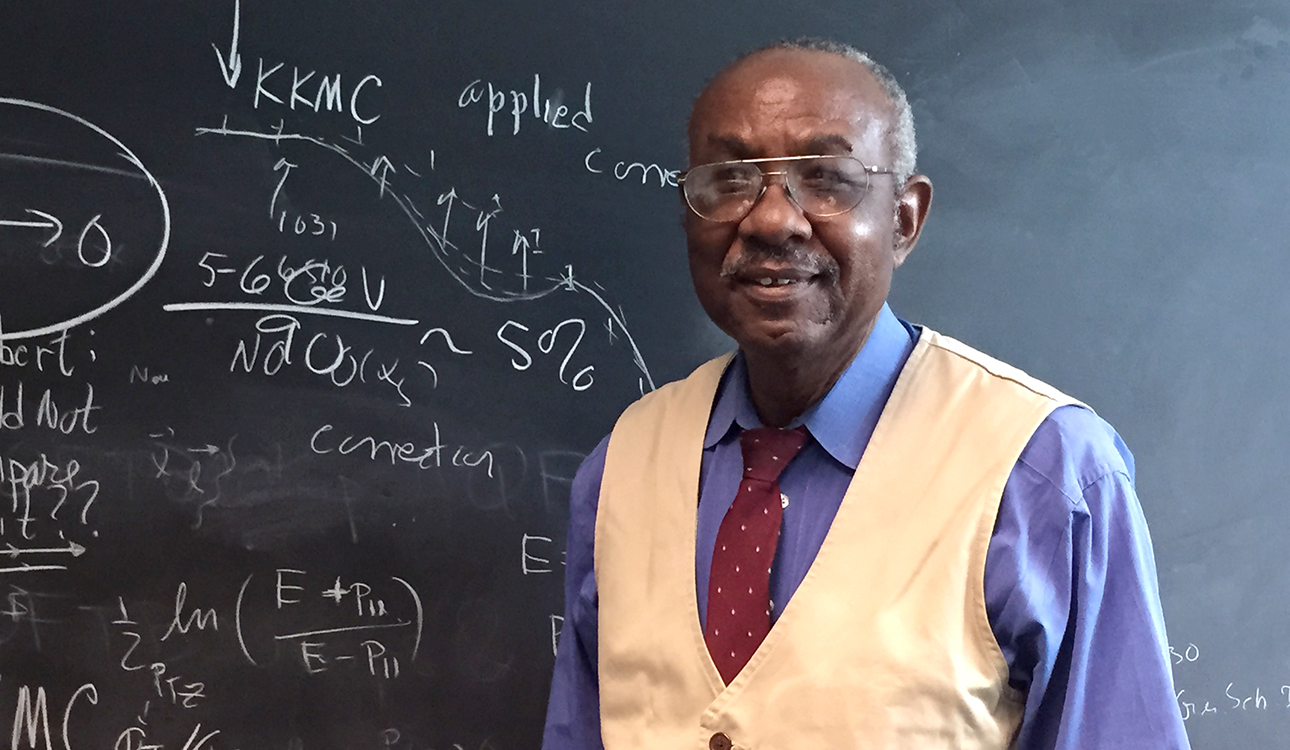

Dr. Bennie Ward, distinguished professor of physics since 2003, has traveled across the country and internationally to teach, research, solve problems in physics, work with the government and on the supercollider in Geneva, Switzerland.

Q: Describe your childhood in segregated Augusta, Ga.

A: It was very interesting. It was racially segregated by law until I was in the 10th grade. Revolutionary in the sense that we could now eat at places where we couldn’t eat, go to movies where we couldn’t go before. Of course, there was some tension in that. But nonetheless, it was a new awakening, so to speak.

I left what had been the all-black high school and went to integrate what had been the premier white high school in the county.

I integrated the baseball team. That got me prepared for being in places where black people haven’t been. That was one of the most advantageous things about my decision to go to that school.

Q: What was it like integrating the baseball team?

A: We really had to train hard. We actually had a very good team. We had really good players on it. I was really good at it also, that was my hobby. Pitching. And I took it very seriously.

I had all kinds of pitches and theories about pitching and ways of making the ball move and putting it where I want to.

When they saw that I could pitch, they wanted me on the team because I could help them win. I never felt there was any issue of me being inferior.

Q: So you used physics to learn how to pitch?

A: I was having a course on physics at the time I was pitching, but I had already developed all that before I had a course in physics.

I understood the different types of forces and how the ball would respond if I would spin it one way versus the other or use one grip versus another. There was a science to it. You might say already that I had an inclination towards those types of ideas and why I liked pitching so much.

Q: Are you excited about baseball season?

A: Always excited about every baseball season. The Dodgers are my favorite team. The A’s I’ve always had an affection for.

A certain senior professor at Purdue also was a passionate fan of baseball. He got Stanford to get World Series tickets. He knew baseball was my passion, and it turns out that was just when the Dodgers and the Oakland Athletics were in the World Series together.

The way they were selling them, you had to buy the whole thing, and he couldn’t go to all three. So he said ok do you want to take one of them? That was amazing. He allowed me to buy them. He offered me the opportunity to take the third ticket, which was quite a privilege because most people don’t get a chance ever to see a World Series game.

That’s the only World Series game I’ve ever been to in my life. Most people don’t even get a chance to go to something like that, especially if they love the sport the way I do.

Q: What is a difference between your generation and today’s generation?

A: The thing that you learn in my time is when you get an extra burden on you is when you work harder. It’s not when you give up. You can do some of your greatest work when people try to put a burden on you.

This is what my parents taught me. The Lord has put you in it because he feels you can deal with it.

A lot of people find themselves in these trying things and they don’t own it. That’s one of the things that strikes me as very different from the people of my generation.

We all had to deal with struggle because we had the integration issue and we had the [Vietnam] war. We learned to work over these types of issues. Confrontation is something that we learned to live with.

Q: What is something interesting you’ve done as a physicist?

A: This was all secret. It was for some very special people back east, in the old Washington D.C., and I was young so I liked the traveling. I really felt like I was doing something useful because of who we were working for and what it was used for.

It was used for the defense of the country. And we did a good job on that.

I had to make a decision. Either I’m going to go 100 percent on these applications of field theory method-inspired activities and make a lot of money, or I’m going to go back to my academic activity and continue to do research and train people who can go out and do this.

I decided that there were some unsolved issues in laws of physics that I really owed it to myself to see what I could do on those. And if I go for this money, I will be giving that up.

Q: What is one of your greatest achievements as a physicist?

A: I think I’ve solved several important problems, some of which have been recognized, some of which have not. The one that I think is the most impressive, and has the least recognition, is my solution for the cosmological constant problem that I put out.

The formula is established using methods I developed and it does something that my adviser used to argue with Dr. [Albert] Einstein about. And that is it shows that quantum mechanics can be used to treat the general theory of relativity without having to change the conditions of the theory. In other words, I don’t have to go to higher dimensional spaces, or change the nature of space and time.

Dr. Einstein thought that was impossible because most of the time all the other attempts to do that have to change something. Like what dimension we live in, or they have to modify the theory of Dr. Einstein.

I’m able to solve that problem with finite answers, predictable results … without having to do that. So I feel some vindication in giving up all that money.

Q: What big projects are you working on right now?

A: Most of my work is concerned with the hadron collider in CERN [European Organization for Nuclear Research]. Most of my work has to do with calculations relating to making precision predictions for the physics of the large hadron collider. And that is now in the process of turning on again.

Q: Why did you choose to become a professor?

A: One has a calling that I believe in the world that you can’t get away from. And you could see I went way away from this when I worked even in the black part of the applications of fundamental physics, but I came back because of my calling.

I had a calling that brought me back, even though it meant giving up a lot of money and other things. I felt like I was blessed with this calling and that I needed to honor it and I tried to do it.

We really need to produce more well trained PhDs in physics if America is going to have any kind of chance of remaining in a leadership role in high technology.

Q: How do you merge physics and Christianity?

A: There is no conflict between them because the beauty of physics is that the more you understand it, the more you understand that there are some phenomena that transcend it. And that can only be addressed through faith.

The laws of physics can describe the phenomena in the world, as we can perceive it. But when you probe deeply into these laws, you understand that they are limited. The idea of life and death is simply beyond the laws of physics.