Dane Chronister | Reporter

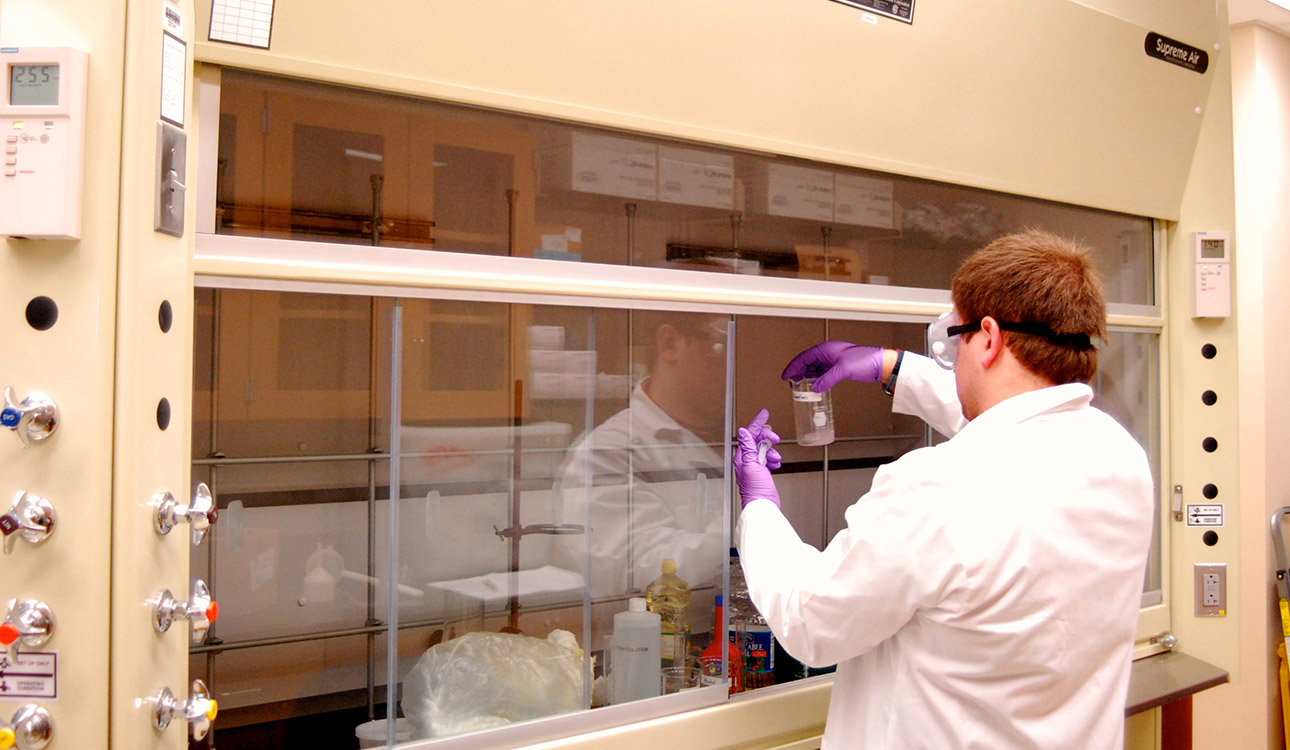

Monday in a laboratory of the Baylor Sciences Building.

Dane Chronister | Reporter

By Dane Chronister

Reporter

Pearland sophomore Mark McComb and Dr. Larry Lehr, senior lecturer of environmental science, took their biodiesel project to the Baylor Science Building’s labs for the first time last week in order to grasp better understanding its abilities.

In the next few weeks, Lehr and McComb plan to travel to Abilene Christian University in order to work with the biodiesel reactor alongside another group of scientists to see what they need to improve or change in their own process.

Through a process known as transesterification, vegetable oils, animal fats and used restaurant that can be used in diesel engines as an alternate, renewable form of energy. grease are converted into biodiesel.

“This chemical reaction conversion long-chain mono alkyl esters or fatty acid methyl esters which compose biodiesel when used as a fuel,” McComb said.

The B20 blend is 20 percent biodiesel and 80 percent petroleum. With the use of this form of biodiesel, engine upgrades do not need to be made because the majority of the biodiesel is still petroleum.

For Baylor’s environmental goals and for McComb’s experimental purposes, B20 would be the most cost-effective and available form of biodiesel.

Pure biodiesel is the cleanest form of fuel that burns the least amount of pollution, but would call for engine conversions.

Using this B20 version of fuel allows for the extension of current oil supplies by reducing the percentage of petroleum diesel that is consumed, since 20 percent of the product is biodiesel.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s website, “Biodiesel will gel in cold weather, just like regular diesel fuel. But B20 can be treated for winter use, in similar ways that No. 2 diesel is treated. Using B20 throughout the winter months just takes a little preparation and good fuel management practices.”

McComb said he hopes that Baylor’s campus transportation could one day run primarily on this form of renewable energy.

Ingredients in his experiment included a stock solution for the titration, which consisted of one liter of distilled water and one gram of catalyst, which is a Potassium Hydroxide solution. He also used 99 percent Isopropyl Alcohol, four drops of Phenolphthalein, one milliliter of cooking oil and 250 milliliters of Methanol to create Methoxide.

with his new biofuel.

Dane Chronister | Reporter

McComb created biodiesel that will later be sent to a lab for testing required by the Environmental Protection Agency for safe and protected usage.

“Even though Mark is a sophomore, he is motivated and capable of handling this project. It’s great because I can step out of the lab, if I ever need to, and know that Mark is going to be safe and not blow you guys up,” Lehr said.

Even as they worked in the lab for this new breakthrough in energy, Lehr warned McComb against being careless and irresponsible.

The gallon-to-gallon yield of the B20 biodiesel is around eight percent more energy than regular diesel gasoline and fewer nitrates are produced in the pollution process.

“One of the benefits of using biodiesel is it’s a lot better on the engine. It’s cleaner, it lubricates the oil better and it helps your engine run more smoothly, especially for older diesel engine that don’t have the best working catalytic converters,” McComb said.

He used a 99 percent alcohol instead of 91 percent, which had no drastic effect on the experiment. He also found that for every liter of cooking oil or fry grease, 7.2 grams of catalyst would be needed to make the proper conversion.

“It’s really cool being a sophomore and being able to do research because I don’t know a lot of sophomores or even undergrads that get to do this kind of research this early. I could possibly make my career,” McComb said.