By Taylor Griffin

Arts & Entertainment Editor

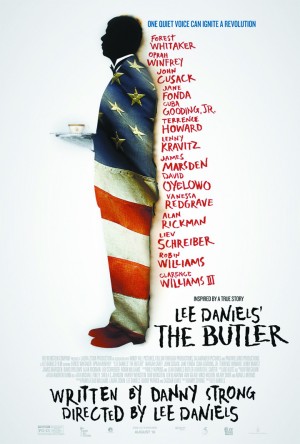

Set during a time that drastically overhauled the American societal landscape, “Lee Daniels’ The Butler,” released on Aug. 16, is a bold move in the way of touching on issues most people would rather forget. However, in this biopic, director Daniels neither excels in storytelling nor disappoints in whistleblowing.

The plot follows Cecil Gaines (Forest Whitaker), a black house servant born on a cotton farm in the South, and his long-time-coming journey to employment as head butler in the White House. During his lengthy tenure, he serves every president from Eisenhower to Reagan, collecting insightful views of each.

On top of which, Cecil and his family are thrust into the swell of the black civil rights movement of the ‘60s. He finds himself struggling to make a name for himself and simultaneously keep the status quo. At the presidents’ individual faults—as well as the world around him—Cecil is acknowledged more for his obedience and servitude rather than his personhood.

The plot was inspired by a profile in the Washington Post of real-life presidential butler Eugene Allen, which remains much more colorful and eloquently presented than its movie counterpart. In this snapshot of his tenure, Allen is described as not just a black butler serving several presidents but a man whisked into the fires of prejudice.

Since its conception, the film has received plenty of previewing speculation and criticism, both good and bad. While it’s getting buzz, I’m doubtful of any true Oscar potential; there’s nothing overwhelmingly comparable to other contenders that pull depth and emotion from unexplored places. “The Butler” so fervently attempts to create but ultimately lacks finesse quite common—and somewhat necessary—in award-winning flicks.

Whitaker, however, truly becomes this man he portrays. He presents a stone quietness in his presence as Cecil that in its reclusiveness, is potent enough to save the movie’s lost ground.

The presidential figures, while pillars to the story, were certainly not put in the best light, some portrayed so far as antagonistic.

Considering the work of Daniel Day Lewis as Lincoln or Kennedy a la Greg Kinnear, there’s an unmistakably high expectation for historical figures portrayed in film. With a laundry list of leading actors in supporting roles, the movie becomes not only jumbled but, even worse, lost. Squinting just the right amount makes Robin Williams an almost believable Eisenhower.

Artificially made facial profiles and stumbling regional accents gave way for laughable cameos from 10 too many notable actors. Besides the predominantly-black ensemble cast, the rest only received fleeting moments of screen time, for better or worse. Alan Rickman’s oily, jet-black coiffure and rough American speak as Reagan was as embarrassing to watch as it was to see Jane Fonda play a clean-cut conservative Nancy Reagan.

Some movies take a while to pick up speed, but “The Butler” lags in spots that need not as much explanation as it gives. The film’s laziness also hits in its fast-paced parts. Following Nixon’s resignation, it doesn’t exactly perk up after a pathetic fast-forward montage of the “unimportant” Ford and Carter administrations.

From there until the end, it gets sloppy and contrived, delving too much time into his life following his time at the White House. An ending solely revolving around the election of the first black president would suffice.

In light of its faults, the movie also hits high points that when done correctly, is powerful. Through his work with the film “Precious,” Daniels shows his ambition and fearlessness in portraying unmentionable topics in dramatic form; same applies to “The Butler.”

Throughout the entirety of the film, the juxtaposition of Cecil’s white-gloved tidiness as a servant in the White House and his son’s guerrilla fighting and protesting in the Black Panther movement sets an explicit metaphor of the ‘60s—skin color aside.

However cumbersome in key points, “The Butler” confronts points of societal tension that are inarguably truthful, providing at its core a poetic allegory rather than a diatribe against black oppression. While it is layered in bouts of humor, heartbreak and good spirits, it speeds up in places that should be savored and stagnates parts that require only a few remarks.

“The Butler” is as overt as it is insensitive, which reflects much of the attitude during these tumultuous times. That said, it accurately and thoughtfully portrays the turbulence of the civil rights movement—a narrative that, quite frankly, is long overdue.