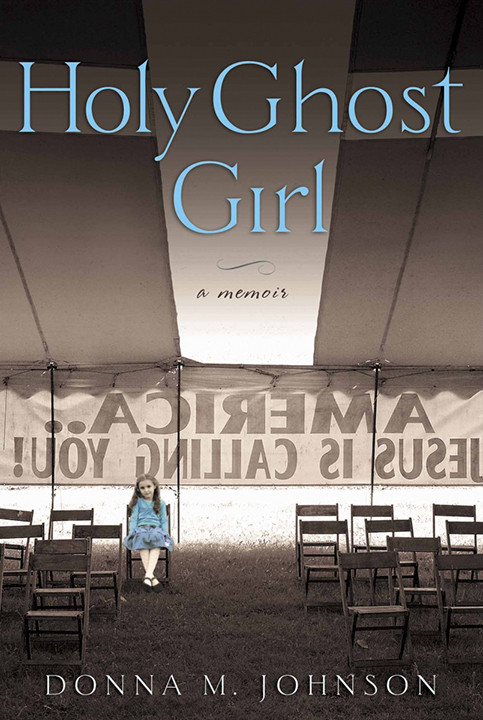

(Courtesy Art)

Editor-in-chief

Chekhov’s gun is canon law for the dramatic principle of foreshadowing. It goes a little like this: If a loaded gun is mentioned in the opening of a story, before the story is over, the gun must be used. Otherwise, it should be omitted.

In opening “Holy Ghost Girl,” Donna Johnson places a loaded gun in the mind of the reader, recounting a phone call from her sister in which she hears tent revivalist preacher David Terrell’s plans to raise his son Randall from the dead. The call recalls Johnson to her childhood, and the next time we see Terrell, it’s in Johnson’s memories.

“Holy Ghost Girl” is the story of Johnson’s childhood on the Sawdust Trail, a circuit of tent revivals she traveled with a group of revivalists, her mother and her younger brother Gary. Though Johnson is the narrator, the story is really Terrell’s. Absent from the stage, it is clear he is still the principal actor, as his every action affects Johnson and indeed, a whole community of “Terrellites” who believe Terrell’s word is holy law.

In an era where religion — and its place in society — are at the forefront of our national consciousness, Johnson’s memoir serves as a cautionary tale. The paradox evident throughout the narrative is a devotion to the Christian God, but an inability to lead a life of Christian standards on anything but a surface level. Saints under the lights of the revival tent, those who put on the mantle of holiness, take it off to commit adultery behind closed doors and smokescreen tales.

Johnson’s own mother is guilty, as is Terrell, though both are publicly religious. Terrell, a “con man, a prophet and performer,” is also the closest thing Johnson has to a father.

Though he is the lover of her mother and eventual father of Johnson’s half-sisters, Terrell never quite achieves relation to Johnson herself. His marriage to her mother is hollow and imaginary, existing nowhere but the mind of her mother, who follows him throughout Johnson’s years as a child, sometimes leaving Johnson and her brother to suffer maltreatment at the hands of believers she barely knows.

Johnson suffers from physical abuse and neglect while staying with Sister Waters, a sinister believer who every night kicked Johnson’s brother “to the john, saying it was time for him to learn to pee in the pot” while Johnson and the other children cried and tried to stop her. She is forced to eat her own vomit at the hands of Sister Coleman. And during her time with the Smiths (no one quite knows how the children wound up there), she is forced to fake a conversion experience to be allowed to use the restroom.

This apparent paradox — this life of darkness and light, sin alongside outward holiness — is ultimately what leads Johnson herself to abandon the church at 17, becoming instead “a doubt-ridden Episcopalian with Buddhist tendencies.”

Despite her troubled childhood, Johnson forgives Terrell and her mother again and again. “Holy Ghost Girl” is a look at Terrell’s world through the eyes of a child, without apparent skepticism or anger. Her lack of vitriol is the most noticeable feature of the book. In some ways, this is an incredible feat. Johnson, who shows an impressive ability to divorce herself from emotion in her tale, manages to avoid the easy way out, shaping her mother and Terrell into real, fully human characters instead of using the book as a platform for ax-grinding (which could have been warranted, given her treatment).

I would characterize her approach as mature. To fill her pages with latent bitterness and paint her mother and Terrell as villains fails to recognize the human truth that even those who commit heinous crimes are, in fact, people.

Terrell and her mother achieve a kind of redemption through Johnson’s characterization.

However, her lack of bitterness also left me wondering what thoughts and feelings Johnson herself experienced in evaluating her childhood. Neither her mother nor Terrell were held to scrutiny, and she also consistently fails to explain miracles the magical Terrell allegedly performs. For example, there is the story of The Woman Who Used to Be Big, whose mysteriously large and distended stomach disappears when Terrell touches her. Curiously, after her healing, her skirt falls to the ground, and she is left nearly naked in front of the congregation, a suggestion, perhaps, of Terrell’s real motivation.

Johnson’s loaded gun reappears in the closing of the book, during the funeral scene. Through her childhood, miracles are never examined, but until now, the question of real or not real hasn’t been quite so pressing. Those Terrell healed might not have had real problems in the first place. But Randall’s death — his very real death — was no stunt. He had been suffering for years with a hemorrhagic condition.

When a miracle is truly necessary, the gun misfires. Terrell himself doesn’t even attempt the resurrection. It is this that suggests to me of all the things Johnson labels Terrell as, “con man” is the foremost.

It’s a good book, but one that, like Terrell’s ministry, only scratches the surface of something much bigger and more profound, a book that fails to value absolute truth among what is holy. But some ideas aren’t worth sacrificing to the truth. The idea of the father, the idea of miracles — should these be laid on the altar and offered up? Based on Johnson’s treatment of these figures when she recounts her childhood, I’d say she thinks not.