McClatchy Washington Bureau by Michael Doyle

By Michael Doyle

McClatchy Newspapers

WASHINGTON – The Justice Department stayed silent when Indiana and Washington state strengthened their voter identification rules. But when Georgia and Texas lawmakers wanted to do the same, they needed federal approval.

Now, this different treatment for different states will face a make-or-break test at the Supreme Court. In a potentially landmark case, justices on Wednesday will consider whether it’s time to dismantle a key plank of the historic 1965 Voting Rights Act.

“This case presents questions that cut to the very core of our democracy,” said Caroline Frederickson, president of the liberal-leaning American Constitution Society.

Passed when state-sanctioned racism was at its most insidious, the Voting Rights Act contains multiple elements designed to root out discriminatory practices. The entire law, originally spanning 19 sections, is not at risk of repeal in the case being heard Wednesday. Instead, the case arising out of Shelby County, Ala., centers primarily on two muscular sections that happen to have the biggest reach, and that the county is challenging.

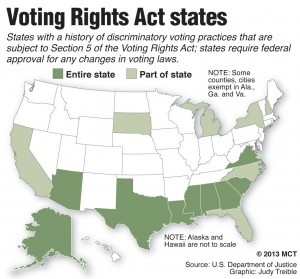

The tool is called preclearance. Under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, designated states and jurisdictions must secure Justice Department approval before they change any voting practice or procedure. This can cover everything from buying new voting machines and closing polling places, to requiring photo IDs and shifting district boundaries.

A related section provides the formula for determining which political jurisdictions must meet the preclearance requirements.

Nine states are currently covered in their entirety: Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, Texas, Alaska, Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi and Virginia. Selected jurisdictions of an additional seven states are also covered, including parts of California, Florida, North Carolina, Michigan, New Hampshire, New York and South Dakota. The law, though revised several times since 1965, still pegs preclearance coverage in part to voting turnout or registration in the 1964, 1968 and 1972 elections.

“The question is whether Congress needs to update this, so that if you’re going to treat states differently, then you are going to need current evidence,” said Carrie Severino, chief counsel of the conservative Judicial Crisis Network.

In addressing this question, the court will be measuring the preclearance rules against the 15th Amendment’s declaration that Congress can take “appropriate” measures to enforce equal voting rights. As often happens, the meaning of “appropriate” is in the eye of the beholder.

The case also pits states against one another, sometimes surprisingly. South Carolina and Georgia joined two other states in a brief supporting Shelby County. Texas and Alaska added their own, similar briefs.

On the other side, North Carolina and Mississippi joined California and New York in urging the court to retain the current law, saying in a legal brief that “the substantial benefits of the preclearance process have outweighed its burdens.”

The preclearance process is extensive.

Each year, meeting what Severino dubbed a “Mother may I?” obligation, states and localities submit between 4,000 and 6,000 preclearance requests to the Justice Department. Especially in the past, the process rooted out questionable maneuvers.

In 2001, for instance, federal officials objected when the all-white council of Kilmichael, Miss., tried to cancel an election shortly after African-Americans became a town majority. Instead, in a special election, voters subsequently elected four African-American candidates.

“The Voting Rights Act remains a necessary vehicle to protect the most fundamental right we have in this democracy,” said Rep. Mel Watt, D-N.C., who helped rewrite the law in 2006.

Lawmakers in 1965 originally described preclearance as a temporary measure, saying in the official 1965 House of Representatives report that they expected that preclearance “would no longer be needed” by 1970. Nonetheless, preclearance has been extended in five consecutive rewrites of the law. The 2006 rewrite extends it for an additional 25 years.

“Congress saw substantial evidence of continuing discrimination,” NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund attorney Debo Adegbile said Friday. “The remedy is clearly necessary. … It’s strong medicine for a strong problem.”

Supporters of the law further stress that covered jurisdictions can bail out – avoid its demands – if they can show there was no voting discrimination in the prior 10 years. One hundred and ninety jurisdictions have bailed out so far.

Everyone agrees there’s been progress. In 1965, fewer than 20 percent of eligible African-American residents of Alabama were registered to vote. There were no African-Americans in the state legislature. Voting registration has skyrocketed since, and African-American members now account for about a quarter of the state legislature.

“Nothing in the record suggests that covered jurisdictions remain engaged in the pervasive voting discrimination and electoral gamesmanship that once made case-by-base adjudication of constitutional violations a futile enterprise and spurred Congress to act,” Shelby County’s attorney, Bert Rein, wrote in a brief. “Current conditions cannot justify preclearance.”

The Shelby County challenge is following a 2009 challenge raised by a small Austin, Texas-area utilities district. Though the court in 2009 left the Voting Rights Act intact, Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., in words that now read like a foreshadowing, warned that preclearance’s days might be numbered.

“The statute’s coverage formula is based on data that is now more than 35 years old,” Roberts wrote, “and there is considerable evidence that it fails to account for current political conditions.”