Editor’s Note: This is an article in our ongoing “Great Video Game” series in which readers and staffers alike are asked to submit a few hundred words about a video game that they consider to be great.

By Lance Cahill

Guest Contributor

Leo Strauss once noted that the distinction between Athenian and Roman political philosophers animated the crucial conclusions that derived from reason and revelation. These differences noted, I am willing to say that Hobbes and Augustine would both unequivocally agree that “NASCAR Thunder 2003” is the greatest racing video game ever made.

What engenders such ecumenical agreement, the skeptic asks. The magical blend EA Sports perfected was between two competing conceptions of ‘the good’: Authenticity and playability.

A purist for the former might be happy playing Sierra Sports’ “NASCAR Racing 4” — essentially “Flight Simulator” for rednecks — and a slacker who prefers the latter would be happy playing a game with more quarters than Curtis Jackson III and more grease deposits than Louie Anderson: the “Cruis’n USA” arcade series.

As someone who had difficulty getting his virtual Cesna 172 off the tarmac and hated the idea of cruising anywhere, let alone California, I needed something different.

I found the right mix with “NASCAR Thunder.” The game developers took handling seriously without every corner turning into a car ride with Billy Joel.

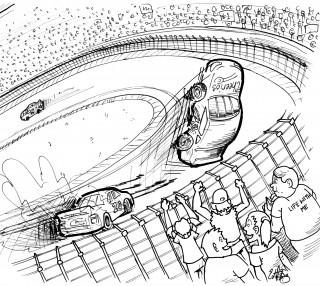

A great feature of the game was “Lightning Challenges” where you got to re-enact classic moments in the past five years of NASCAR history, such as near accidents (my favorite) or come-from-the-back victories. While these “Lightning Challenges” were intrinsically valuable, they also unlocked cool features like additional paint designs and classic drivers, such as Tiny Lund!

The neat thing about “NASCAR Thunder” was the ability to own your own team and guide it through 20 years of sponsorship changes, competitor retirements, and personal triumph.

As someone who spent his time simulating “Madden” seasons, I would have appreciated a more in-depth owner mode in the 2003 version.

However, the accumulative nature of the career mode allows for uplifting anecdotes to tell your friends in moments of personal doubt and uncertainty, such as the time when you passed nine cars in the final two laps at Darlington to win the race.

Not only has “NASCAR Thunder” taught me all I needed to know about life, but it has also taught me all I need to know about risk.

Many of the sponsorships in the game require you to meet certain performance metrics.

A choice must be made: Do you wish to be paid for every top 10 finish (a higher dollar amount) or to be paid as long as you maintain an average finish above 15th (a lower dollar amount)?

Informational completeness is an issue here and so the risk-neutral player has difficulty deciding, but the choices are clear to the risk-loving and risk-averse player.

The developers of the game have subsequently ignored my suggestions for an options market to sufficiently hedge this risk, but I digress.

While the graphic queens might snicker at the quality of “NASCAR Thunder 2003,” it is still a game worth taking for a test drive — or on a magic carpet ride as Steppenwolf recommends to those who have dared to “dream…/right between the sound machine” and played “NASCAR Thunder 2003.”

Does reading this article make you think of a video game that you consider great? Please send us an email at lariat@baylor.edu with a suggestion for a “Great Video Game.” Please include a few hundred words on why you consider your game to be great and you just might find your opinion here.