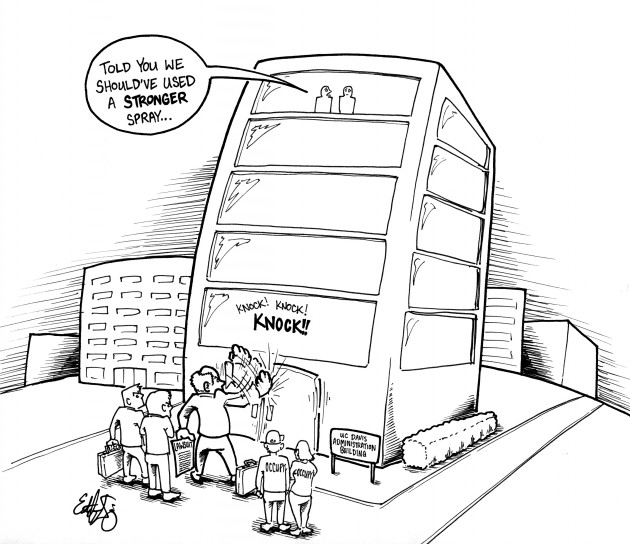

The streams of rust-colored pepper spray shot at Occupy protesters at the University of California, Davis may have obscured their vision, but they also made one thing clear — speech is not always free.

Campus police sprayed the peaceful protesters at close range on Nov. 18 as they sat huddled in an on-campus protest, refusing to move despite “orders to disperse,” according to the Associated Press.

YouTube videos of the incident show protesters trying to shield their faces as the officers spray them repeatedly and even tug at them, trying to break them apart.

The videos show a sickening display of unnecessary police force against a group of students simply expressing their views.

But those sprayed took what could be a step toward justice when they sued the school’s chancellor, Linda Katehi, and other campus administrators Feb. 22. With the suit, they are “seeking unspecified damages” as well as campus policies to help safeguard nonviolent protesters from similar situations in the future, the AP reported.

The protesters feel that their constitutional rights were violated, and it seems clear that they were.

Associated Press

If a group of university students cannot demonstrate peacefully on its own campus, one has to wonder where they can. Universities should be places open to the free expression of views, the consideration of various angles of an issue.

It is within our country’s universities that so many young people figure out where they stand on moral, social, theological and philosophical issues. Many of those issues are tough and controversial. Some stem from nationwide debates; others, local ones. But students have the right to debate each of these issues.

Universities should rejoice when students take the initiative and become involved enough in these conversations to take a stand, to start a protest.

But that also means respecting students’ freedom of speech, which is essential for students to form their stances and understand all sides of each issue.

Hopefully this lawsuit will indeed lead to compensation for the protesters as well as new campus policies that ensure future protesters’ freedoms are uninhibited.

Outside the courtroom, UC Davis president Mark Yudof has launched an investigation into police methods of handling student protests at all 10 University of California campuses.

A report on Yudof’s investigation is due in March and will hopefully come guidelines that protect not only student protesters’ rights, but also their safety.

The school has also taken initiative in creating a task force led by former California Supreme Court Justice Cruz Reynoso, a professor emeritus at the UC Davis School of Law. The task force is looking into the incident and preparing a report — to be ready in early March — that will also include “recommendations to prevent similar incidents.”

Hopefully these recommendations will actually be implemented, as a sign to students — both current and future — that UC Davis wants to right the situation and improve its policies for the generations to come.

Surely the U.S. District Court in Sacramento, where the lawsuit was filed, will also stand behind the students and ensure that new policies are created and upheld effectively.

The issues at hand may not become less complex with time, and we as a nation will almost certainly never all see eye-to-eye. But the right to speak freely and the right to protest should be rights we can all agree upon and exercise.

The U.S. District Court in Sacramento and the administrators of UC Davis themselves can take one step toward getting us there by safeguarding those rights for its own students.